Visualizing the Future of the Public Safety Beat

Table of Contents

Introduction

As newsrooms across the country have publicly and privately grappled with their approach to crime and criminal legal reporting since George Floyd’s murder in 2020, much of the focus has been on the words that populate the reporting: the language used, the sources quoted, and the assumptions made. Despite their importance, far less attention has been paid to the images in these stories. Print and digital news stories typically begin with an image that sets the tone for the piece, and television news is, of course, a visual medium with images from beginning to end. The images used in most of these stories reinforce the sensationalism and bias that has long plagued the public safety beat.

This project is meant to be a resource for reporters, editors, photojournalists, art directors, and anyone else involved in producing and selecting the images in news stories. It catalogs the types of images that commonly appear in public safety reporting, offers guidance for how to choose images that tell a more holistic story about the people and places impacted by crime and the criminal legal system, and provides a behind-the-scenes look at the image selection process in a leading outlet covering gun violence and public safety.

I.

Taking Stock of the Status Quo

The images found in stories about crime and the criminal legal system tend to fit into one of the following categories:

- Images of police and policing equipment

- Images of confinement and control

- Examples: barbed wire, prison gates, guard towers, bars, restraints

- Images of people accused or convicted of crimes

While these images may appear to be straightforward, they contain numerous but subtle biases, including that they:

- Emphasize people who respond to crime over people impacted by crime;

- Imply that policing and other forms of punishment are inherently linked to public safety;

- Perpetuate harmful racial stereotypes;

- Dehumanize people accused or convicted of crimes; and

- Sensationalize crime.

Photographs of police are perhaps the most pervasive image in public safety reporting. Of course, there are some instances in which this makes sense: a profile of a new police chief, a story about a new policing tactic, an investigation of police violence. But images of police are also used in stories that are not directly related to policing at all. They show up in stories about crime rates, shoplifting, criminal legal reform, homelessness, overdose deaths, and on and on.

These images pose two problems. First, they emphasize people who respond to crime over people impacted by crime. Stories about gun homicide and other acts of violence often feature images of police and other first responders rather than the people harmed or their loved ones. These choices draw attention away from the heart of the story. Second, they imply that policing is inherently linked to public safety, serving as a subtle, if unintentional, endorsement of policing. In fact, there are myriad ways to respond to crime and other types of harm, and communities across the country are trying out new approaches: unarmed crisis intervention workers, violence interrupters, expanded drug treatment, supportive housing, etc… But images of those people and programs rarely show up in public safety reporting. By continuing to default to images of police, journalists circumscribe the policy responses to crime that people can imagine.

The images of people (other than police) that appear in public safety reporting pose an additional set of problems. First, they often perpetuate racial stereotypes. Because Black people are disproportionately arrested and those arrests are disproportionately covered by the news media, many of the mugshots that appear in the news are of Black people. These images, like the stories they appear in, prime negative racial stereotypes. Fortunately, newsrooms across the country have begun to recognize this problem. Many have restricted their use of mugshots, often citing the presumption of innocence and the harm done to communities of color.

A great deal has been written about the use of mugshots and the steps that many newsrooms have taken to end or limit their use, so we will not go into further detail in this report. For those interested in learning more about recent trends in the use of mugshots, see these pieces from Poynter, The Marshall Project, and NiemanLab. For those interested in hearing directly from newsrooms who have limited the use of mugshots, see these pieces from Cleveland.com, the (Biloxi) Sun Herald, and the Orlando Sentinel.

It’s not just mugshots that dehumanize people accused or convicted of crimes. Stories about crime and the criminal legal system often feature images of people in handcuffs, wearing jumpsuits, or behind bars. Those images reduce people to what is likely one of the worst experiences of their lives. While images of people in court, jail, or prison may make sense for some stories, the composition of these images often presents people in a menacing light, compounding their dehumanizing effect. Images that were perhaps intended as a more humane alternative to mugshots, like stock photos of anonymous individuals, are often no better. A disembodied image of a pair of hands in cuffs literally reduces a person to their experience with the criminal legal system.

These editorial choices are united by one central theme: they sensationalize crime with lurid or alarming images. Of course, tragic and frightening things happen that warrant media coverage, but the role of journalists is not to stoke fear or to make a spectacle of any given crime. According to their own mission statements, the job of media outlets is to help people understand the world. Sensationalized images do little to help people understand what drives crime and what works to reduce it. Even more troublingly, these images don’t just show up in stories about serious harm; they also appear in stories that aren’t about threats to public safety at all. For example, the lead image in this story about declining crime rates is of people allegedly stealing from a mall. A story that is meant to inform people about a reduction in crime leads with an image that contradicts its message.

In a rapidly changing media landscape that is increasingly focused on visuals, photojournalists and editors have the opportunity to rethink the images they use to tell stories about public safety. The following sections offer recommendations for selecting images and examples of pathbreaking photojournalism from news outlets across the country.

II.

Sharpening the Focus of Public Safety Images

The public safety beat is broad, covering everything from neighborhood shootings and police violence to prison healthcare and legislation about bail policy. That said, public safety stories do tend to fall into a handful of categories. Below, we’ve laid out those categories along with recommendations for selecting appropriate images and real-world examples for each. We have also included a list of general recommendations for image selection in public safety reporting.

General recommendations

-

- Lead with empathy and transparency. Talk to people before you take any photographs, and always be clear about the purpose of the image and the context in which it will appear.

- Consider using illustrations when original and stock photography aren’t options or don’t make sense.

- Think about the mood of the image in an effort to avoid reinforcing stereotypes. Does the subject look menacing or approachable? Agitated or calm? This is particularly important when selecting photographs of people of color who have a long history of being portrayed in a threatening light by the news media.

- Choose images that depict the day-to-day life of your subjects, rather than just the lowest moments of their lives. This might be challenging in jails and prisons, but it is possible. In those settings, consider asking subjects where and how they spend most of their time (reading, working, exercising, etc…) and photograph those activities or the places where they happen rather than falling back on images of bars, handcuffs, and razor wire.

- Ensure that the tone of the image matches the content of the story. For example, if a story is about a decline in crime rates, choose an image that sets a positive tone.

- Avoid photos of police officers or police equipment in stories that are not directly about policing. Instead, choose images that more directly depict the people and places impacted by the events of the story.

- Do not use mugshots.

Story-specific recommendations

-

In stories about individual crimes, consider featuring images of…

1. People impacted by the event (i.e. victims/survivors, family members and friends of victims/survivors, witnesses, neighbors, etc…). If you are in touch with people impacted by the event, don’t be afraid to ask if they want to be photographed. Many people want to tell their story, even in tragic cases, but it’s essential to lead with empathy, transparency, and mutual agreement on the style and use of the images. That said, it may not be appropriate or possible to use images of the people impacted by the event. In some cases, people may not want to be photographed because they feel it will be re-traumatizing or that it could put them at risk for more violence. And sometimes you won’t be able to identify an individual to photograph at all. If using a photo of a person is not possible, consider one of the options below.

-

2. The location where the event occurred. To avoid a seemingly-anonymous streetscape, include a detail, like a street sign, recognizable landmark, or even telephone lines.

-

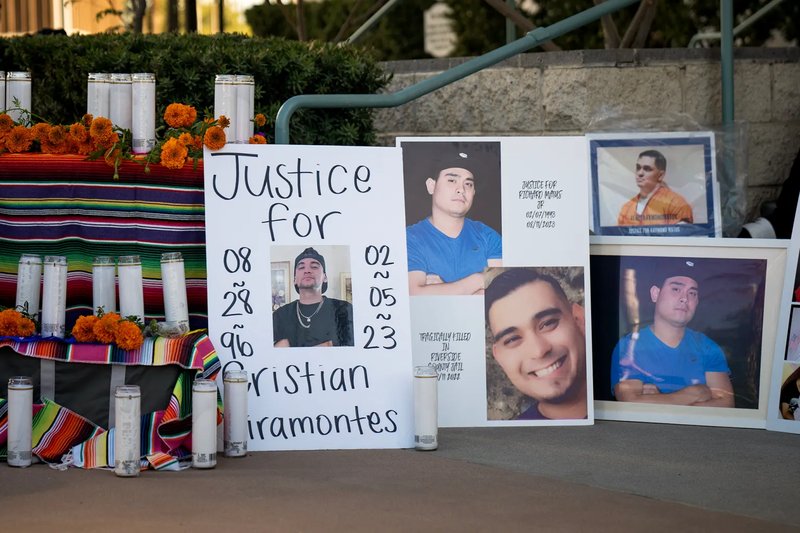

3. Vigils, protests, or memorials. After some time has passed, you may be able to photograph objects that memorialize the people impacted by the event, such as signs, candles, cards, vigils, graffiti, etc…

-

Breaking news stories about individual crimes typically have little information beyond a brief description of the alleged crime and the name of the victim and/or accused. These stories are among the most likely to rely on mugshots or generic stock photos of police. This is likely due in part to the fact that it can be difficult to contact the people impacted by the event or access the location where it happened on a tight deadline. It's worth considering whether the factors that make it difficult to identify appropriate images for these stories are indicative of a larger problem with this style of reporting. For more on the issues with daily crime beat stories, along with alternative appraoches to covering public safety, see Chapter 1 of our report Building a Better Beat.

-

In stories about crime trends, consider featuring…

1. Images of the neighborhood or community that the story is about. Ensure that the tone of the image matches the tone of the story. For example, if crime is trending upward, demonstrate how that is affecting the community (i.e. empty streets, residential or commercial security devices, memorials, etc…). If crime is trending downward, demonstrate how that is affecting the community (i.e. busy streets/parks, open doors/windows, neighborhood gatherings, people talking on the sidewalk, etc…).

-

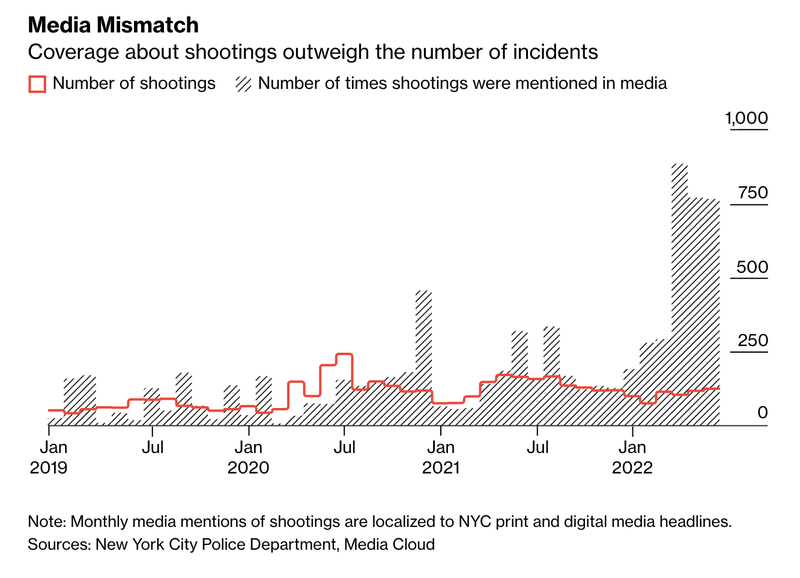

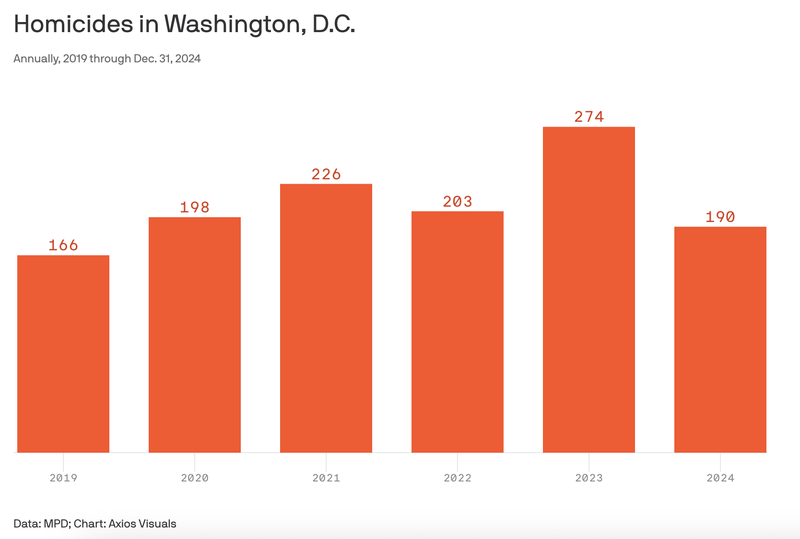

2. Data visualizations or illustrations. When images of local communities aren’t appropriate (for example, in stories about national crime trends) or possible, data visualizations and illustrations can help people understand the direction and magnitude of the trends.

-

In stories about criminal legal policies, consider featuring images of…

1. The policy being implemented in the real world. Criminal legal policies play out on the streets and in courthouses, jails, prisons, and community organizations across the country. When possible, photograph people experiencing the effects of the policy.

-

2. A location relevant to the policy. If it’s not possible to capture people in the image, photograph the place or community where the policy is put into practice (i.e. community center, school, courthouse, jail/prison, etc…).

-

In stories about harmful aspects of the criminal legal system, consider featuring …

1. Images of directly impacted people. When photographing incarcerated or formerly incarcerated people, ask for their input in composing the photograph, and avoid emphasizing stereotypical or sensational elements of the situation (handcuffs, tattoos, bars, etc…). Ask for old photographs that illustrate the subject’s day-to-day life before their arrest or incarceration. If an incarcerated subject is not able or willing to be photographed, consider asking their friends or family members if they could pose for a photograph instead.

-

2. Images of vigils, protests or memorials. See guidance above for photographing these sites.

-

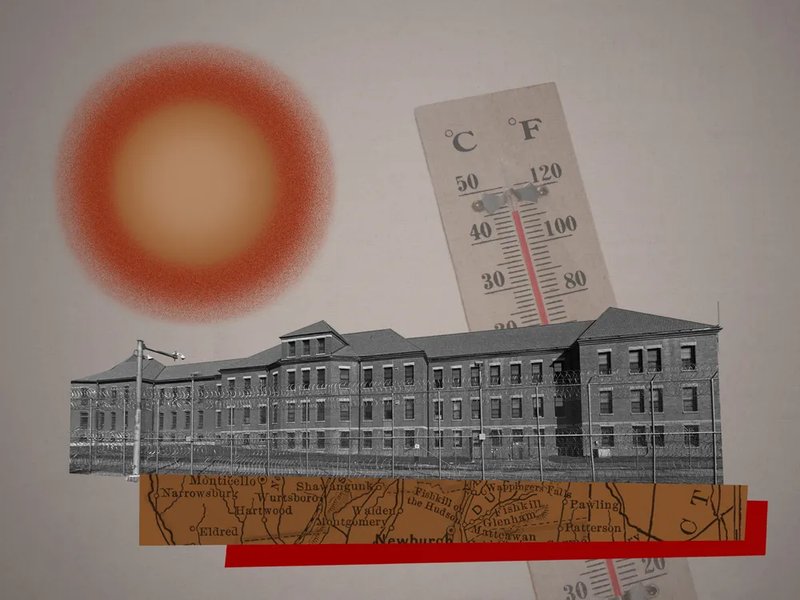

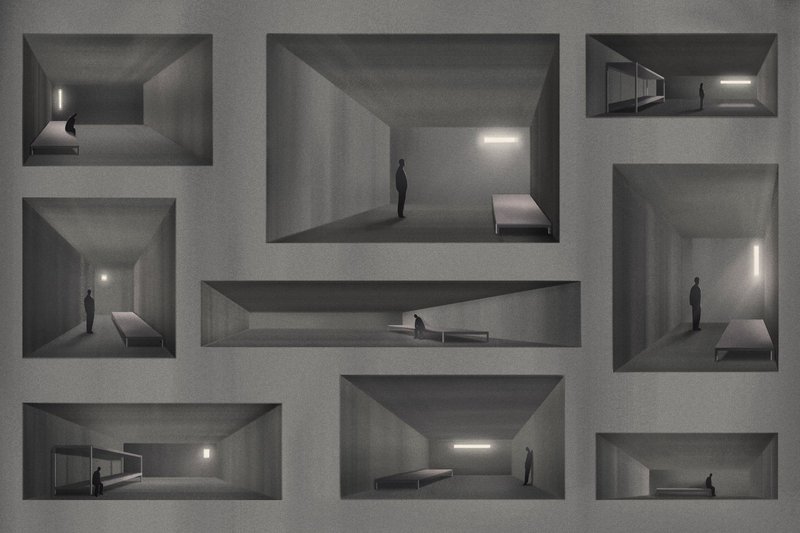

3. Images of a location relevant to the story or policy. When photographing jails and prisons, try to focus on the details that are relevant to the story, rather than falling back on sensationalized images of the buildings, like armed guard towers, razor wire, or seemingly endless rows of bars. For example, try to photograph fans or blankets if the story is about extreme heat or cold, the cafeteria if the story is about food quality, the infirmary if the story is about injury or illness, the size and condition of the cell if the story is about solitary confinement, etc…

-

4. Illustrations. Accessing the places that criminal legal policies play out, like police headquarters, courtrooms, jails, and prisons, can be difficult. If you can’t get access to them, consider commissioning an illustration that captures the tone and theme of the story.

III.

Learning from the Pros

Tips on Composition from Award-Winning Photojournalist Andrea Bruce

Photojournalists have a particularly important role to play in helping people develop a more accurate and nuanced understanding of crime and the criminal legal system, and that role comes with significant challenges. Moving away from sensationalized images, like police tape and razorwire, in favor of neighborhood scenes and prison interiors may sound dull or inert, but it doesn’t have to be. Below is a list of tips for composing beautiful and compelling images from Andrea Bruce, a seasoned photojournalist with experience capturing images for stories about a wide range of public safety issues.

- Prioritize specificity. This is best done by choosing an image that illustrates something unique to the story. But even if the image you choose isn’t directly related to the story, ensure that it contains a specific detail that draws the viewer’s eye.

- Think of how the viewer enters the photo. Allow their eyes to travel back in the scene with perspective lines. Think of a road leading back to the horizon from where you stand.

- Look at all corners of the frame to ensure you don’t have bright, distracting elements in the photograph.

- Lighting adds beauty and mood. Sunrise/sunset light is ideal. Or, try nighttime images with street lights.

- Combining several elements that layer the image gives people more to look at. Think of trees in the foreground, the road in the background. A bike in the foreground, houses in the background.

Lessons from Selin Thomas, Art Director at The Trace

In addition to the general recommendations and guidance provided in this report, reporters, editors, photojournalists, and others can learn from art directors at outlets that are changing public safety reporting one image at a time. One such publication is The Trace, a nonprofit newsroom with a team of journalists exclusively dedicated to reporting on the United States’ gun violence crisis. Below are some of the guidelines they use in their work and examples of how they use imagery “to improve public understanding, increase accountability, and identify solutions that can lead to safer homes and communities for all Americans.”

This guidance was written by Selin Thomas, who is a senior editor at The Trace, where she leads the newsroom's production processes, serves as photo editor for stories, and manages ongoing coverage areas. She is also a contributing feature writer.

At The Trace, we are exclusively dedicated to covering gun violence, so we deal with issues of how to accurately and ethically represent crime and justice — and the people at their center — everyday. As The Trace’s art director, I’ve taken lessons from other outlets, colleagues, photographers, and perhaps most importantly from the daily execution of the work itself. It’s not always possible to commission or access the perfect image; missteps are part of the process. But I’ve found certain guidelines helpful in keeping the quality and appearance of our work consistent and compelling.

Brainstorming the ideal image

In trying to bridge the gap between the text of a given story and the impression made and left by the story’s visuals, my work first involves pulling out the most basic information, or understanding the who, what, why, where, and when. Then, I read a bit more deeply into (or directly ask about) its more abstract themes, arguments, and context. This may include gleaning the motivations of the reporter and editor in covering the story for our newsroom; placing it in the wider context of existing coverage; looking for indications of when and why the reporting took the turns it did; and paying close attention to the sources chosen to represent the story. All of this information helps me understand the visual needs — to what extent can an image grab someone’s attention, prompt them to click, and reflect the core of the story?

Finding the best image

As a newsroom, we are rarely chasing breaking news, which allows us to be sensitive to the timing of a shooting and its depiction in our written and visual work. We consider victims and survivors first. We practice skepticism of the powers that be, the criminal justice system, and the official line, and therefore do not rely upon imagery of gun violence itself, its grisly aftermath, or of officials carrying out the duties of law enforcement unless it serves the story. Instead, we depend on our photo commissions and wire image subscriptions to scour for more realistic photos of daily life that give the reader a sense of place and people. If the story is tied to mass violence, we focus on images that show the feelings of those close to it, or that illustrate (sometimes abstractly) the response. When policy or law is involved, we commission illustrations that simplify complexities and show potential effects on daily life. Unless necessary, we avoid imagery that shows guns in use, and we never use imagery (photos or illustrations) that shows a gun pointing at another person. We also consider alleged perpetrators, and don’t use mug shots or perp-walk photos; instead, we try to direct the readers’ attention to another aspect of the proceedings, such as the victims, public response, a neighborhood, or a community leader.

Ethically navigating the transaction

Journalism, and especially photography, is transactional. In this work, we are often asking people to speak on the most difficult events of their lives — and allow us to photograph them as they do it, sometimes in places that are emotionally fraught. That work is important; it takes the reader closer to the ground, provides a platform, and hopefully holds leaders accountable to those with the least power. But as an industry, we’ve come a long way in realizing that work is not more important than that person’s survival, or even their comfort. In commissioning photography of those affected by gun violence, we prefer to work with photographers who are familiar with sensitive topics, or The Trace’s work specifically, and who live where the story takes place.

We make sure to open dialogue with them about our newsroom’s specifications, as well as what specific aspects of the subjects’ experience they should be aware of, in order to make the subject(s) as comfortable as possible. We advocate for an empowering photo-taking process that often involves the photographer talking with the reporter directly before reaching out to the photo subject. Rather than instructing them, we include the subject in the process and let them know that they are free to take breaks or end the session. We make it as convenient as we can for their location and schedule. While we don’t preview any part of our editorial work to sources, we do try to get a sense of what the person's comfortable with and their preferences for representing their story and take those into account.

We also keep evergreen images (for example, general city, neighborhood, and hospital photos) for future use.

Selecting the final image(s)

By the end of an art direction process in collaboration with a photographer, I have a solid read on the final story and how the visual process went overall. I select a first batch mostly on impulse — “What’s grabbing me? What are the best composed and most focused images? Which photos have tension?” A lot of good stuff (that doesn’t serve this particular story) will be left on the cutting room floor. Of the narrow selects, I’ll look for one representative image for the lead, waiting for the final headline and dek before making a firm decision, and select other in-line photos based on the flow of the text, particularly looking to make connections with quotes, section breaks, and key findings of the story. More still will be left behind, and sometimes they can be used later. But in the end, the last person on my mind is the reader — how did I get their attention and how can I keep it?

When it comes to selecting a wire image, I’m looking for key people in the story, different representations of the story than have been published before, or more place-oriented (sometimes older) images that better reflect the story’s core.

Below, I've explained the decision-making process behind the lead images in a handful of stories that ran in The Trace.

Despite having a handful of strong potential lead images for this 2024 public health feature story, I chose this image because it clearly illustrated an individual loss. More poignantly, the field of graves could be representative of the thousands of others, though their deaths are not related to this story. Finally — and this is deep within the story — Carrie Hickles could not afford to buy her daughter’s headstone, which illustrated the economic marginalization that contributed to her daughter’s death and so many like it, and the hardship surviving family members face in pursuing justice in their cases.

Biden’s Gun Violence Prevention Office Is Empty. Here’s How Its Work Can Continue Under Trump.

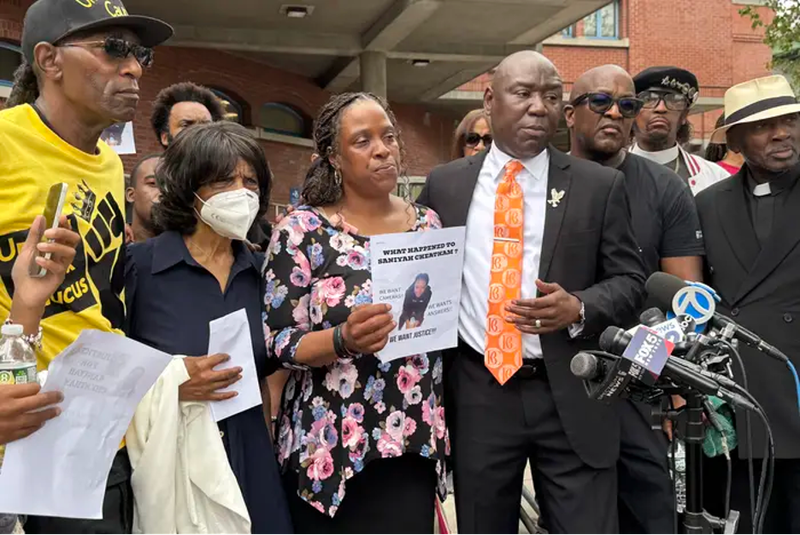

This photo simultaneously captures the effect gun violence can have on a single person — a mother, holding a clearly identifiable photo of her son — and the significance of that mother’s engagement with executive leadership and federal policy. It captures the small and the large, which makes the shuttering of the White House’s first Office of Violence Prevention more poignant.

In 2019, Congress Finally Funded Gun Violence Research. Here’s How It’s Changed the Field

I found this photo after the headline was already finalized, which can often be an advantage. Other than getting a photo of Congressional activity — a bit dry — there weren’t many direct visual options, but I was intent on finding a photo that took the reader beyond the halls of power or the institutions conducting the research, and back onto the ground where these decisions affected the lives of everyday people. I’d had this image saved in my ‘evergreen catalogue’ of AP images that I refer to when I’m in need of something more abstract. It worked particularly well because the motion of the people illustrates the motion of ‘change’ in the headline, and the street illustrates the ‘field’; most importantly, it shows the civic action that resulted from a mass shooting that altered the trajectory of the country.

Just Outside the School Gate, America’s Gun Violence Epidemic Surrounds Its Students

This story was conceived as a kind of antidote to the oversaturation of media coverage of mass shootings, especially school shootings, which are just a fraction of the nation’s gun violence. For the assignment, we sent out a photographer we work with in Chicago regularly, Akilah Townsend, a native of the city whose portfolio includes colorful, empowering portraits, which is what initially drew me to her work. Akilah knew how to capture the essence of the data analysis provided in the reporting: how prevalent shootings are in the communities around schools. We wanted to illustrate the potential of a school — its true purpose — and the terrifying possibility of that potential being gunned down.

He Fatally Shot a White Man, Claiming Self Defense. Now He’s Charged With Murder.

For this story, we sent out a Philly-based photographer whom we work with a lot, Kristen Jae Bethel. Because he was in custody, it wasn’t possible to get photographs of Maurice Byrd, the person at the center of the story and shooting – so we approached it as a kind of Frank Sinatra Has a Cold challenge, and photographed all that surrounded the man before he fatally shot a neighbor. For the lead, we chose a quiet image of his now-empty storefront, which is quintessentially American, to help illustrate the disruption of small-town life and, with the headline, the complexities of social and racial interactions in suburban America. We followed up on this story a year later, when Byrd was acquitted of the charges, and chose a photo we already had from the previous shoot of the parking lot where the shooting took place to help illustrate the mundanity of gun violence.

The photographer in this case, Daniel Lozada, was able to accompany our reporter Josiah Bates while he was reporting in Cleveland, which always helps. They spent a bit of time at an after-school program designed to keep kids busy, active, and away from violence. In an echo of the Chicago schools story, I liked this image for the lead because it shows the potential of children to thrive, with some safety and attention, and it makes the possibility of their deaths by firearm that much more horrific. The story is about local groups that have been working for decades to ensure that kind of programming, and the continued challenges they face in sustaining it, so to see young kids engaging with it — and possibly saving their lives amid startling rates of youth violence — is all the more powerful.

IV.

Using Stock Photography

Stories about the inner workings of jails and prisons are among the most difficult to visualize in a nuanced and compelling manner. We’ve offered recommendations and examples above for photographing jails, prisons, and the people who live and work in them. However, that is often not possible. Journalists – particularly photojournalists – are rarely allowed inside these facilities, and incarcerated people are almost never allowed to take or share photographs from inside.

Stock photography is one alternative to original photos, but these images tend to be dehumanizing and sensationalistic. We have identified stock photographs of jails and prisons that avoid those pitfalls in the galleries below.