Building a Better Beat: A New Approach to Public Safety Reporting

Table of Contents

Introduction

Chapter 1: Distorting the Landscape of Harm

Chapter 2: Sensationalism

Chapter 3: Reinforcing Stereotypes

Chapter 4: Serving as a mouthpiece for police, prosecutors, and other criminal legal officials

Note: More chapters to come as we roll out the full report.

Introduction

1 The criteria used to select these institutions are described in the methodology section at the end of this report.

2 We excluded "excellence" and "integrity" from our analysis, as some version of those themes appeared in nearly every single mission statement, and they are abstract concepts that are difficult to define and measure.

This project is an effort to measure the realities of contemporary crime reporting against the goals and values of journalism. To do that, we must first understand what those goals and values are. We reviewed the mission statements of 45 journalism institutions1 and found that the seven most frequently cited themes2 in those mission statements were:

-

“The truth matters. At the end of the day it may be the only thing that matters. Finding it is our job, and our pledge to anyone who takes the time to read or watch or listen to what we’ve found out.” The Boston Globe

-

“Hold accuracy sacrosanct.” Reuters

-

“Our mission is to deliver the truth every day.” New York Daily News

-

“We are truth-seekers and storytellers.” CNN

-

“We seek the truth and help people understand the world.” The New York Times

-

“Star Tribune covers more of what matters to Minnesota, all day, every day – helping us stay informed, and navigate and take part in our world.” Star Tribune

-

“TIME's mission is [...] to provide context and understanding to the issues and events that define our times.” TIME

-

“USA TODAY's mission is to serve as a forum for better understanding[.]” USA TODAY

-

“We bring you the stories that matter most, written without bias[.]” Chicago Tribune

-

“The newspaper shall not be the ally of any special interest, but shall be fair and free and wholesome in its outlook on public affairs and public men.” The Washington Post

-

“The Atlantic will be the organ of no party or clique, but will honestly endeavor to be the exponent of what its conductors believe to be the American idea.” The Atlantic

-

“In all our work, we believe in continually asking questions, seeking out different perspectives and searching for better ways of doing things.” The New York Times

-

“We are based in one of the world’s most diverse places and strive to reflect that in our organization and in the work that we do. We believe that diversity is a source of strength: When people from different backgrounds join together to face challenges, solve problems and tell stories, we serve our community better and do better work.” Los Angeles Times

-

“[W]e [...] [i]nclude a diversity of voices that are not always part of the conversation.” HuffPost

-

“[W]e break big stories and set the news agenda.” New York Post

-

“The newsroom has no agenda; other than to serve our readers with a steady dose of important, relevant news.” Tampa Bay Times

-

“Through print, online and events, The Hill’s powerhouse of vehicles signal the important issues of the moment, and together have earned the reputation of being a complete and comprehensive source of Congressional news.” The Hill

-

“We are passionate about making our community strong and more prosperous.” The Dallas Morning News

-

“[W]e help make Milwaukee and Wisconsin even better places to live.” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel

-

“PBS empowers individuals to achieve their potential and strengthen the social, democratic, and cultural health of the U.S.” PBS

-

“The Seattle Times is anchored in public service that improves our community.” The Seattle Times

-

“We have a unique, trusted responsibility as a watchdog and custodian.” The Wall Street Journal

-

“We will be vigilant watchdogs of government and institutions that affect the public[.]” Gannett (via The Arizona Republic)

-

“By telling these stories to, about and for a wide mosaic of people, journalists and PR professionals strive to hold institutions accountable[.]” University of Southern California Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism

Many common practices in contemporary crime reporting do not uphold these values. Too often, stories about crime contain inaccuracies, obscure the causes of and most promising solutions to violence and harm, and prioritize the perspectives of powerful actors in the criminal legal system.

A consistent feature of contemporary crime reporting is its tendency to link safety with policing, prosecution, and punishment. This happens at every stage of the journalistic process, from story selection and sourcing to substance and stylistic choices. Sometimes the connection is obvious (for example, a story suggesting without evidence that bail reform is causing an increase in gun violence), but often it’s far more subtle. For example:

-

The small number of crimes that police track–index crimes–are far more likely to be covered by reporters than other violations of civil or criminal law that impact as many or far more people each year, like wage theft, housing discrimination, price fixing, building code violations, tax evasion, illegal chemical emissions, and crimes committed by prison guards, prosecutors, and police.

-

Articles about index crime trends routinely mention changes to criminal legal policies, like a new police task force or a shift in a local prosecutor’s charging practices, absent any evidence that those policies significantly impact public safety.

-

Quotes from police officers, prosecutors, and corrections officials dominate crime coverage, and those individuals’ claims are not always fact-checked or contextualized, even if they have made inaccurate statements in the past. Experts on the macro-level causes of crime and the people successfully implementing other approaches to addressing violence and other kinds of harm are quoted less frequently and less prominently.

-

Language choices, like the “officer involved shooting” euphemism, send the signal that violence committed by government officials happens passively or is not crime.

These and many other practices, documented below, leave readers and viewers with a distorted understanding of what most significantly impacts their overall safety. They also give the inaccurate impression that public safety is inextricably linked with a small range of policy interventions found in the narrow world of police, prosecutors, and prisons, despite the wealth of evidence that those systems do not address the underlying causes of crime, are relatively ineffective at reducing violence and other types of harm, and have enormous social and financial costs.

The impact of these media practices is profound, influencing everything from public policy and our collective sense of safety to the dignity and well-being of people who are directly impacted by crime, policing, and imprisonment. Today, just like 40 years ago, major surveys show widespread public misperceptions of crime. Public and political responses to harm remain instinctively linked to after-the-fact punishment of individual lawbreakers despite overwhelming evidence linking public safety instead to systemic problems of inequality, housing, health care, pollution, and addiction. Of course, the news media does not bear sole responsibility for the gap between perception and reality, but journalism is a part of the broader ecosystem that reinforces the failing status quo and is uniquely positioned to challenge that status quo with evidence and critical context.

This report catalogs pervasive problems with contemporary crime reporting, offers concrete suggestions for improving reporting on public safety issues, and provides examples of newsrooms across the country who are already making inspiring changes.

Chapter 1:

Distorting the landscape of harm

News outlets devote a lot of column space and airtime to index crimes, the crimes tracked and recorded by police departments. These crimes–murder, rape, robbery, aggravated assault, burglary, larceny, and motor vehicle theft–were chosen to be the country’s primary measure of public safety by police officials in the 1930s, and they remain so today, nearly 100 years later. Index crimes undoubtedly cause harm, but they are far from the only threats to personal and community safety. The news media largely reinforces this overemphasis on a small subset of overall crime in its public safety coverage, leaving people anxious about certain kinds of crime and in the dark about other important safety issues in their communities.

How does this show up in the news?

Prioritizing coverage of the crimes tracked by police relative to other crimes and non-criminal public safety issues

Reporting on arrests and allegations of criminal conduct

The following is a series of headlines that ran within a single two-week period in late 2021 from the 25 largest cities in the United States.

- Cops make arrest in fatal shooting outside Inwood restaurant: officials New York Daily News

- 3 arrested after brazen smash-and-grab attempt at Nordstrom at the Grove Los Angeles Times

- 2 Michigan men held after car hit Indiana officer’s car head-on, police say Chicago Tribune

- No Bail For Two Men Charged With Killing 3, Including Armored Car Guard And Two Accomplices, During ‘Murderous Spree’ On South Side CBS Chicago

- Two men arrested after charged with murder in unrelated shootings in Houston Houston Chronicle

- PD: Man accused of killing brother at Phoenix home ABC15 Arizona

- Murder charges filed against man accused of shooting his ex-girlfriend as she walked with her young twins The Philadelphia Inquirer

- 3 arrested in Llano County after pointing "AR-15" at another car NEWS4SA

- Man arrested after 4s Ranch deputies found 100 bottles of stolen liquor inside vehicle ABC 10 News San Diego

- Man arrested on murder charge in Deep Ellum gunfire exchange that killed 2, wounded 4 in September The Dallas Morning News

- San Jose: Police arrest man on suspicion of August shooting The Mercury News

- 4 Caldwell High students indicted in connection with school bus incident KXAN

- Police: Woman charged with murder in fatal shooting of woman on Jacksonville’s Westside CBS47 Jacksonville

- Fort Worth man arrested in connection to fatal shooting outside homeless shelter in May Fort Worth Star-Telegram

- Cellphone leads police to suspect in killing of ex-lawyer in South Linden The Columbus Dispatch

- ‘Broken system’: Indy man arrested for another robbery after being sentenced to supervised release Fox59 Indianapolis

- 17-year-old Charlotte teen arrested for 5 armed robberies WCNC Charlotte

- Four arrested in seizure of illegal weapons and drugs in S.F. San Francisco Chronicle

- Man accused of driving drunk, pistol-whipping dog and shooting at another man in Union Gap The Seattle Times

- Aurora police arrest man for fatal shooting Sunday that killed 18-year-old The Denver Post

- Chevy Chase private music teacher accused of fondling two students The Washington Post

- Woman charged with making online threat against Green Hill High School WKRN Nashville

- Police Make Arrest After String Of Armed Robberies In OKC, Del City News9 Oklahoma City

- El Paso firefighter arrested, accused of claiming to be fire marshal at Five Points bar El Paso Times

- 15-year-old boy arrested with loaded gun in Roxbury The Boston Globe

- Wasco County shooting suspect nabbed in Skamania County KOIN Portland

Why It Matters

The news media’s disproportionate focus on index crimes–the narrow subset of crimes that police most closely track and record–obscures the broader landscape of safety in a few different ways. First, these news stories are often sourced from police reports or press releases and thus only capture the instances of these crimes that are reported to and taken seriously by the police. The majority of sexual assaults and acts of domestic violence are never reported to the police at all, often because people do not trust the police to do anything about what happened to them. Most of the assaults, rapes, and murders committed by the police themselves and those committed inside the more than 6,100 local, state, and federal jails, prisons, and immigrant detention centers across the U.S. don’t make it into police reports. Policy choices also skew the crimes tracked by police. For example, in public schools with embedded police officers, minor altercations between students are often recorded as crimes, while in private schools, similar fights are rarely brought to the attention of police. Thus, the traditional crime beat paints an incomplete and biased picture of even the small subset of crimes on which it focuses.

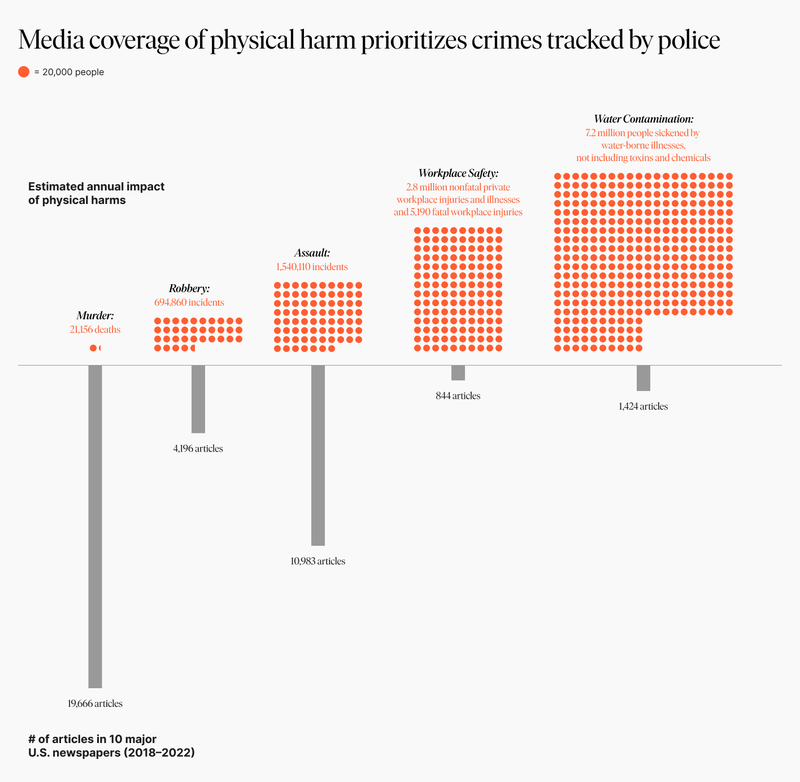

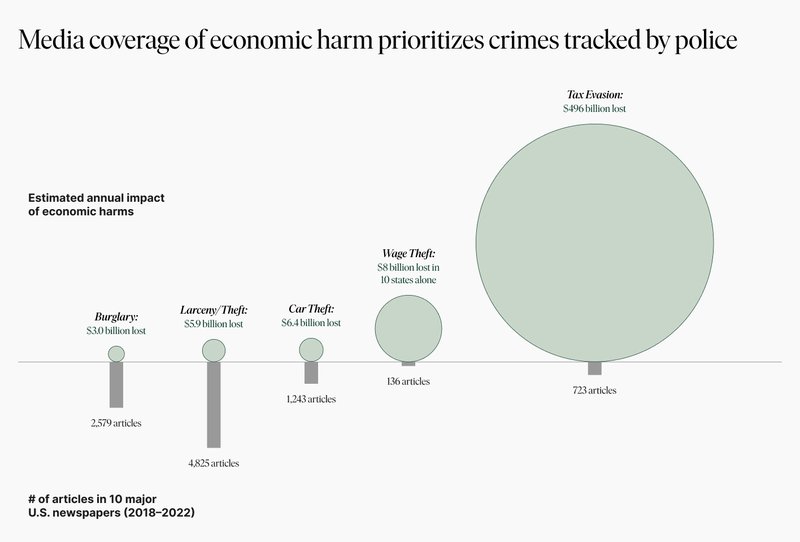

More broadly, index crimes represent a small portion of total illegal activity and an even smaller portion of the harm experienced by people every day. Violations of civil and criminal law that impact millions of people each year—like wage theft, housing discrimination, price fixing, building code violations, tax evasion, and illegal chemical emissions—are not routinely tracked by the police and thus command far less news coverage than index crimes. The government agencies and courts that document these pervasive legal violations often do not have public relations departments whose job is to communicate with news outlets like many police departments and prosecutors’ offices, especially those in large cities, do. Nor do news outlets choose to have dedicated beat reporters searching for and reporting on these legal violations each day. The vast majority of these crimes are simply lost to history. The public does not learn about and therefore does not treat with the same urgency these threats that affect their safety as much or more than index crimes.

And the same pattern holds true for the even broader array of safety issues that are not civil or criminal legal violations, such as the number of people who die or contract serious illness each day because they lack access to health care or housing. While a new generation of criminologists has begun to talk about the importance of considering the broader category of “harm” rather than the narrow category of index crime, the news media has largely not followed suit. To take just one example, lead pollution makes people sick and alters brain development in ways that lead to more violent crime, but there is very little local or national daily news reporting on lead content testing in water and soil compared to the volume of news stories about individual violent crimes.

In addition to obscuring the broader landscape of harm, media coverage of index crimes often focuses on a highly unreliable metric: arrests. Most arrests are simply not newsworthy, because so many criminal charges are declined or dismissed by prosecutors. In New York City, nearly 50% of arrests do not end in a conviction. This is not just true for large, progressive cities. Thirty-seven percent of charges are dismissed each year in Alabama, and roughly one-quarter are dismissed in Arizona and Utah. Because arrests and charges are not strong predictors of the outcome of a case, news stories about them have limited value to the public but can have lifelong consequences, like difficulty securing housing or employment, for people whose charges are eventually dropped.

It’s no surprise, then, that public perceptions of both crime and harm are out of sync with reality. Year after year, people believe that index crime rates are increasing, even though they have been declining for most of the last 25 years. And people overestimate the likelihood that they will be the victim of an index crime while underestimating the risks posed by other threats to their health and safety. Simply put, if one of the central goals of journalism is to help people understand the world, contemporary U.S. news coverage of crime is not achieving its objectives. In fact, it leads to significant failures of public education about the things that most matter to people’s safety and well-being.

Alternative Approaches

-

Audit the number of stories in your beat dedicated to particular types of crimes.

See examples

Bloomberg published an analysis of the number of news stories about shootings relative to the number of shootings in New York City.

-

Dramatically reduce the number of anecdotal stories about index crimes, especially those focused on arrests and allegations.

Where it’s happening

Gannett has pledged to focus on trends, rather than running stories on individual crimes, and to stop relying on police blotters.

-

When individual cases are covered, cover the case from beginning to end, ensuring that dismissals are covered as prominently as convictions.

Where it’s happening

Gannett has committed to follow the cases they choose to cover through to the end.

-

Provide context on each stage of a criminal case and the likelihood that an arrest or charge will be downgraded or dismissed.

Remove identifying details and images of people who are arrested or charged with crimes.

Where it’s happening

The AP and Cleveland.com say that they will no longer publish the names of people charged with minor crimes.

-

Expand the mission of crime beats to include a broader range of issues that impact people’s safety.

How to do it

Our team has compiled a resource bank with governmental and non-governmental sources of information about a wide range of safety issues, including housing conditions, OSHA violations, wage theft, environmental hazards, crimes committed inside jails and prisons, and many others.

-

See examples

-

The Boston Globe: Research finds stark racial disparities in how Boston responds to unhealthy conditions that trigger asthma

-

ABC13 Houston: 13 Investigates: Decade-high inmate deaths just one concern at Harris Co. jail

-

City & State New York: Illegal evictions are rising across the state, but landlords rarely face consequences

-

Minnesota Reformer: There must be something in the water

-

-

Shift resources to beats, sections, and verticals that cover overlooked safety issues.

Where it’s happening

-

The Christian Science Monitor started a new vertical dedicated to covering cybersecurity and privacy, with a focus on online harassment, identity theft, and other personal safety issues.

-

WBUR started a new vertical focused on local environmental issues.

-

The Tampa Bay Times has a section dedicated to toxic algae affecting the region, called Red Tide.

-

The Los Angeles Times has a Housing and Homelessness section.

-

The Minneapolis Star Tribune added a section focused on positive news–solutions to problems and people working to make their communities better.

-

Chapter 2:

Sensationalism

Sensational crime reporting has followed a familiar pattern for more than a century. Even after high-profile journalistic failures (i.e. the Central Park 5 case, the now-debunked superpredator myth), the practices that drove that reporting remain common features of contemporary crime coverage. Like the news media’s overemphasis on the types of crime tracked by police departments, sensationalism contributes to a culture in which people incorrectly believe that crime is almost always rising. These misperceptions drive fear and, in turn, punitive policymaking that has a terrible track record of improving public safety and carries enormous social and financial costs.

How does this show up in the news?

Covering lurid, individual crimes with around-the-clock intensity

Examples of sensationalism in the news

Then

The Lawrence Eagle-Tribune won the 1988 Pulitzer Prize for general reporting for its coverage of Willie Horton, which spanned nearly 200 stories about the case and the Massachusetts furlough system through which Horton had been temporarily released from prison. The story became a centerpiece of the 1988 presidential campaign, and then-Governor (and presidential candidate) Michael Dukakis curtailed eligibility for the state’s furlough program, despite the fact that more than 99% of people released through the program returned to prison without incident. More broadly, this coverage contributed to an increase in public and political support for harsher sentencing laws and fewer release opportunities for people in prison. Those policies have a dismal track record when it comes to improving public safety and cause tremendous harm to people of color and poor people across the United States.

Now

In June 2021, a reporter with a local ABC news affiliate shared a video of a man seemingly filling a garbage bag with stolen products at a Bay Area Walgreens and riding away. The news media published 309 stories about this single shoplifting incident over the following four weeks. Coverage of other shoplifting incidents caught on video followed a similar pattern with similar results. Even though property crime remained similar to pre-pandemic levels, the Governor of California called for hundreds of millions of dollars in additional spending to prosecute retail theft crimes, despite a large body of evidence demonstrating that increased penalties do not deter retail theft and disproportionately impact Black and Hispanic people.

Reporting crime statistics without appropriate context

Each of the examples below is a real headline that was rewritten using the same data cited in the original article.

Using hyperbolic language

Examples of hyperbole in the headlines

- Surge in New York City subway crime fueled by robberies, muggings ABC7 New York

- San Francisco’s Shoplifting Surge The New York Times

- Twin Cities area sees surge in carjackings, putting drivers on edge StarTribune

- SF mayor and district attorney taking action amid retail crime surge ABC7 San Francisco

- Biden Rejects Defund the Police to Cheers From Democrats Facing Crime Wave Newsweek

- New York City crime wave continues into 2022 as city rolls out safety plan CNN

Why It Matters

Sensationalism shows up in both story selection and style. Here’s the standard playbook: newsrooms pick a lurid crime or an alarming crime statistic and use hyperbolic language to tell the story for days on end. These crimes, often pitched as news by police officials, typically feature a white and/or wealthy victim and an alleged perpetrator who is Black and/or an immigrant. Similar harm experienced by poor people and people of color–particularly Black and indigenous people–is ignored or covered far less intensely. Unlike major investigative stories, which usually appear once or a handful of times, these stories result in daily articles and, in the modern context, all-day coverage on cable news with corresponding push notifications.

Serious harm warrants serious coverage, but a large share of these stories do not meet that standard. The stories rarely paint a full picture of the people impacted by the violence or a sober analysis of relevant context, focusing instead on the sensational details of the crime. In the most extreme cases, these stories are presented as representative of an alarming trend that demands action, even when no such trend exists.

Mark Fishman and LynNell Hancock carefully documented how this phenomenon played out in New York City during the 1970s and Denver during the 1990s, respectively. Fishman’s work in Manufacturing the News, “Assembling a Crime Wave,” illustrates this clearly. Fishman was embedded in a newsroom, working on a separate project, and ended up documenting how news reporters at several stations in New York City unintentionally reported – and thus created – a nonexistent "crime wave" in the late 1970s. What began as an attempt by journalists to organize their crime coverage into a compelling theme turned into frequent, sensationalized coverage of violence against the elderly, with more and more incidents being fed directly to newsrooms from the police. There was no actual increase in violence or harm against the elderly during this time period, but that didn’t stop the creation of inevitable new categories of “victims” (typically elderly white people) and “aggressors” (typically young Black and brown men.) Hancock documented another media-concocted “crime wave,” this time surrounding a false narrative of out-of-control youth violence in Denver during the summer of 1993, that resulted in a flurry of punitive legislation dismantling the state’s juvenile justice system, allowing more children to be charged as adults, approving construction of more prisons to house children, and the eliminating parole for children as young as 14.

A similar pattern shows up in stories about crime data. When police departments release index crime data, news coverage often highlights the most sensational statistics–the biggest increases, the highest rates–while downplaying large decreases and record lows. One way this happens is by breaking up crime data into smaller subcategories so that one particular subcategory that is rising can be reported on. For instance, an outlet may report on a rise in carjackings during a particular time interval but ignore decreases in the larger category of robbery. Reporting on crime data also tends to focus on week-to-week, month-to-month, or year-to-year fluctuations and fails to note longer historical trends, which often (but not always) paint a far less alarming picture.

In stories about individual crimes and crime statistics, journalists frequently rely on alarmist language that evokes fear. This is especially true of terms that convey powerful and uncontrollable natural forces, like a “wave” or a “surge.” Metaphors like this are frightening because they imply helplessness at the hands of a powerful force, and when people feel scared, evidence shows that they become more punitive. In fact, scholars have found that the standard script of news stories about crime and violence makes people more likely to support policies like the death penalty and “three strikes” laws. Every year, the evidence base proving that these punitive policies do not actually reduce harm and disproportionately impact poor people and people of color grows larger.

All of these practices distort public opinion and public policy, failing to uphold the values of both public education and serving the public good. Today, the public is ill-equipped to understand increases or decreases in index crime and unaware of many of the programs and policies proven to reduce these crimes and other types of harm.

Alternative Approaches

-

Identify crimes that received multi-story coverage at your news outlet and analyze what those stories have in common.

Prioritize coverage of trends over individual crimes.

See examples

-

Focus on the causes of crime.

See examples

- CNN: 'We've seen lifelong friends kill each other:' How a state capital became one of the deadliest US cities

- NPR: U.S. Gun-related Homicide Rate Jumped Nearly 35% in 2020

- The Guardian: ‘Took a Long Time to Get Here:’ The Women Stopping Gun Violence in Their Communities

- Chicago Reader: Politics of fear: Are youth really to blame for the carjacking spike?

- The Appeal: To Fight Gun Violence, Kids Need Places to Play

-

If using index crime data from police departments, provide context to counter the incomplete and highly curated nature of the information being released by authorities.

How to do it

- Use precise language that indicates the direction and amount of changes instead of vague and dramatic terms like “surge” or “wave.”

- Report on trends across the full range of crimes included in the data.

- Analyze index crime trends over multiple time periods, including a historic comparison to the highs of the 1980s and 90s.

- Compare local index crime trends to what’s happening in other areas of the state, country, and/or world.

- In lengthier stories, include analysis from experts on why the rate of index crime varies across time and place.

- Consider and note the political and policy context in which the data is being released, as well as who is releasing it. For example, are police officials releasing the statistics during negotiations over the police department’s budget or shortly before a vote on bail reform changes that the police union is lobbying against?

- Note the limitations of the data, including the large number of crimes and other forms of harm that are not included.

-

See examples

Chapter 3:

Reinforcing Stereotypes

The stories crime reporters choose to run–and the words and images used in those stories–often reinforce racial, gender, and class stereotypes and have been shown to activate readers’ and viewers’ biases and punitive attitudes. These practices are in direct conflict with the journalistic goal of avoiding bias.

How does this show up in the news?

Disproportionately presenting people of color–especially Black people–as perpetrators of crime and white people as victims of crime.

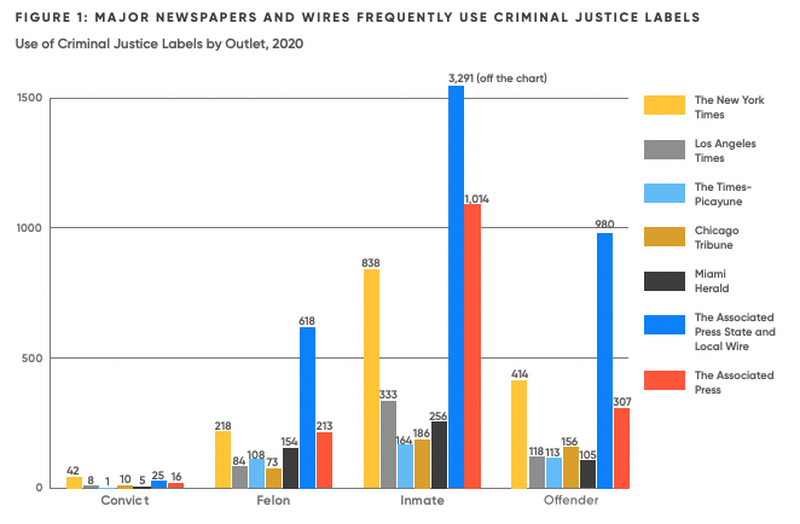

Using words that label people based on their involvement with the criminal legal system, like “felon,” “convict,” and “offender.”

Source: Elderbroom, B. Rose, F., & Towns, Z. (2021). People First: The Use and Impact of Criminal Justice Labels in Media Coverage. FWD.us. https://www.fwd.us/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/PF_PDF_report_final.pdf

Publishing mugshots.

Why It Matters

Contemporary crime reporting largely paints people of color–particularly Black people–as drivers of crime and white people as victims of crime. Studies analyzing news coverage in media markets across the country have found Black people overrepresented and white people underrepresented as perpetrators of crime relative to their actual arrest rates (which are themselves rife with racial bias). Similarly, coverage of missing women and girls varies considerably based on race and employment status, with white women and girls receiving more coverage than women of color and women with jobs in the formal economy receiving more sympathetic coverage than missing sex workers. These choices activate racial stereotypes and increase support for punitive criminal legal policies that are relatively ineffective at reducing harm and disproportionately impact people of color and poor people.

The language and imagery used in these stories create similar problems. People directly impacted by the criminal legal system have been calling for an end to the use of labels like “felon” for decades, because they find them dehumanizing and stigmatizing. On top of the individual harm done, recent research shows that these labels also affect public opinion and public policy. When people are exposed to news stories that rely on labels (“habitual offender”) instead of descriptors (“person with prior convictions”), they are more likely to describe the person in question using negative words like “dangerous” or “scary.” Exposure to these labels also impacts support for criminal legal policies. This research found that support for criminal legal reforms (for example, allowing people with felony convictions to vote or reducing the length of some prison sentences) was roughly 50/50 among people exposed to news articles using neutral descriptors (like “person with a felony conviction”) and was much lower among people exposed to news articles using labels (like “felon”).

Images used in crime stories follow a similar pattern. Because Black people are disproportionately arrested and those arrests are disproportionately covered by the news media, many of the mugshots that appear in the news are of Black people. These images, like the stories they appear in, prime negative racial stereotypes. In addition to these systemic impacts, mugshots harm the individuals in the photographs. Mugshots often remain online and searchable long after a person’s case concludes. For some people, that means their mugshots remain online even if their charges are dropped. For others, it means that the image follows them after they have served a prison sentence and are trying to put their lives back together. In some cases, decades-old mugshots have inhibited people from finding jobs or housing.

All of these practices undermine the common journalistic goal of avoiding bias. After George Floyd was murdered in 2020, news outlets across the country pledged to address the legacy of racism in their workplaces and in their reporting. Reconsidering the stories that are told about crime, and the words and images used to tell them, are essential steps in the process of reducing bias in the newsroom.

Alternative Approaches

-

Audit the proportion of stories at your outlet that portray people of color as perpetrators of crime.

Dramatically reduce the number of anecdotal stories about index crimes. These stories tend to focus on individuals who are either accused of or victims of crime and are thus likely drivers of the types of racial bias described above.

Where it's happening

Gannett has pledged to focus on trends, rather than running stories on individual crimes, and to stop relying on police blotters.

-

Use people-first language.

Where it's happening

- Some outlets, including The Marshall Project, have established a policy for describing people with criminal records.

- The AP Style guide has rules for describing undocumented immigrants and people diagnosed with mental health disorders, which could provide inspiration for similar rules regarding people with criminal records.

-

Stop using mugshots.

Where it's happening

- Poynter: Newsrooms are rethinking their use of mugshots in crime reporting

- The Marshall Project: Newsrooms Rethink a Crime Reporting Staple: The Mugshot

- Cleveland.com: Right to be forgotten: Cleveland.com rolls out process to remove mug shots, names from dated stories about minor crimes

- NiemanLab: No mugshot exploitation here: The New Haven Independent aims to respect the reputations of those arrested in the community it covers

- SunHerald: Why the Sun Herald is changing how it covers crime

- Orlando Sentinel: Gannett stops posting arrest mugshots on several more newspaper websites

Chapter 4:

Serving as a mouthpiece for police, prosecutors, and other criminal legal officials

Newsrooms often rely solely on police, prosecutors, and other criminal legal officials (like prison and jail staff, probation officers, and judges) as the only sources in their crime and public safety coverage. Claims from these sources frequently go unverified, and individual officials and departments that have lied to the public in the past continue to be quoted without disclaimers about their previous unreliability. When other sources are included, the perspectives of those sources, the placement of their quotes, and even the language used to describe them tend to reinforce the police narrative. These choices allow criminal legal officials to disproportionately influence the way that people understand safety in their communities.

How does this show up in the news?

Relying solely or primarily on police, prosecutors, and other criminal legal officials as sources.

Failing to include multiple perspectives that could inform the audience about different views held by people involved in the issue.

Burying perspectives that differ from police and prosecutors at the bottom of the story.

Failing to fact-check or, at a minimum, caveat the unverified nature of claims from police, prosecutors, and other criminal legal officials.

- A lengthy feature about crime in Washington, DC included the false claim by Mayor Muriel Bowser that crime rates in the city were lower when the city had more police officers. After public rebuttals from local experts, The Washington Post corrected the story. Read more at The Washington Post

- Early coverage of the school shooting in Uvalde included myriad false claims from police that were later disproven. Read more at Insider

- Numerous articles cited a change in the Memphis Police Department’s hiring standards as a potential explanation for the police killing of Tyre Nichols. Those articles either do not mention or only mention in passing that most of the officers accused of killing Nichols were hired before the policy change. None of them mention the fact that the two officers hired after the policy change very likely met the original hiring standards. Read more at The Watch

- Police officers in Philadelphia claimed that bystanders failed to intervene while a woman was raped on the subway. That claim turned out to be false. Read more at The Washington Post

- Reporting out of San Francisco amplified statements made by police and D.A. Brooke Jenkins suggesting that her predecessor, Chesa Boudin, had dramatically reduced the number prosecutions in the city, despite publicly available evidence belying that claim. Read more at Mission Local

Relying on police sources with a history of dishonesty.

New York Police Department Commissioner Dermot Shea repeatedly claimed that bail reform was responsible for an increase in crime, despite data from his own department disproving his claim. Even after that data was made public, he continued to make this false claim, and the news media continued to unskeptically publish those claims. See below for a timeline of these events.

Early 2020: NYPD Commissioner Dermot Shea repeatedly blames bail reform for an increase in crime.

- NYPD commissioner links crime spike to bail reform — says judges must be able to hold repeat offenders, New York Daily News

- Spike in January serious crime is fixable, says NYPD Commissioner Shea, Newsday

July 8, 2020: NY Post obtains data that shows Shea’s claims are inaccurate

Late 2020-Mid 2021: Reporters continue to quote Shea making the same false statements without fact checking or noting the documented history of inaccuracy.

- NYPD’s top cop blames bail reform for ‘14-year high’ in NYC shootings, New York Daily News

- NYC Police Commissioner Dermot Shea promises safer 2021 after chaotic year, ABC7

- NYPD: Blame bail reform, not cops, for surging gun violence, ABC10

October 14, 2021: Shea walks back his claims that bail reform caused an increase gun violence when questioned by the legislature

-

During Questioning In Albany, NYPD Commissioner Shea Backtracks On Bail Reform Law As Big Reason For Gun Violence, CBS News New York

November 2021: Reporters continue to quote Shea’s theories about the crime increase without noting his self-admitted history of inaccuracy.

Selectively granting anonymity to police sources.

Failing to include the names of sources prevents readers from learning more about the motivations and credibility of the people doing the talking. Do they have a history of dishonesty? What candidates and legislation have they supported in the past? Are they currently involved in a political campaign or policy advocacy? Moreover, if the information provided turns out to be inaccurate, anonymity prevents readers and other journalists from knowing that these particular sources are not trustworthy and forecloses public accountability for spreading false information in the future.

Quoting sources without disclosing their ties to policing or other conflicts of interest.

Using the passive voice to describe acts of violence committed by police officers.

- Stray Police Bullet Kills Girl as Officers Fire at Suspect in Los Angeles Store The New York Times

- Suspect dies in officer-involved shooting, pursuit in Missoula NBC Montana

- Peaceful Protesters Tear-Gassed To Clear Way For Trump Church Photo-Op NPR

- Journalists blinded, injured, arrested covering George Floyd protests nationwide USA Today

- Police: Officer-Involved Shooting Still Under Investigation The Associated Press

- Two teens were charged with murder in the police shooting that killed an 8-year-old girl at a high school football game The Philadelphia Inquirer

- Police ID 17-Year-Old killed in Downtown Austin Officer-Involved Shooting CBS Austin

- Armed Man Dies After Shooting at Catholic Church in California, Authorities Say The New York Times

Using normative language that is highly subject to interpretation.

- “In her first year as district attorney, Melinda Katz has led major culture shifts in the borough.” The New York Times

- "Rachael Rollins wants to remake the criminal justice system." The Washington Post

- “Alvin Bragg campaigned on lenient policies aimed at making the justice system fairer.” The New York Times

- “Clyde and Garbarino launched the effort to block the policing bill just a day after the Senate voted overwhelmingly to block D.C. legislation updating its century-old criminal code and drastically changing how crimes are defined and sentenced.” The Washington Post

- “With violent crime rates rising in some cities and elections looming, their attempts to roll back the tough-on-crime policies of the 1990s are increasingly under attack — from familiar critics on the right, but also from onetime allies within the Democratic Party.” The New York Times

Why It Matters

Each of these practices above is an issue in and of itself, but they also reinforce one another in ways that add up to a problem larger than the sum of its parts: a media environment that uncritically reflects the perspectives of police. This environment undermines two of the core values of journalism: accuracy and impartiality. We’ll take a closer look at how these practices compromise those values below.

First up: accuracy. This is simple. Police, prosecutors, and other criminal legal system actors have a long, indisputable track record of purposefully lying and otherwise disseminating inaccurate information. Sometimes those lies become big new stories when they are uncovered by bystander video, body camera footage, or whistleblowers, as in the case of the murders of George Floyd and Tyre Nichols or the police response to the Uvalde school shooting. Sometimes lies and inaccuracies come to light many years after the fact, when it’s too late for journalists to meaningfully correct the record. Buzzfeed uncovered 62 examples of police reports that did not match video footage of the interactions, the vast majority of which received limited media coverage until this investigation. And it is far from certain that individual police officers who lie to the media will be treated with skepticism the next time around. In fact, CNN recently hired John Miller, the NYPD’s former Deputy Commissioner of Intelligence & Counterterrorism for the New York Police Department, who lied under oath about the well-documented existence of a surveillance program targeting Muslim people in the wake of 9/11.

Next up: impartiality. Police, prosecutors, and other people who work in the criminal legal system are not neutral arbiters of fact; they are a powerful interest group with professional and financial incentives, political views, and policy goals. While there is, of course, some diversity of opinion across this group, prosecutors’ associations, police unions, and correctional officer unions have a long history of coordinated political activity, from endorsing and financially supporting candidates to lobbying for and against legislation. Like other interest groups, police departments and prosecutors’ offices focus time and money on strategic communications. For example, a Los Angeles Times investigation found that the Los Angeles Police Department and the Los Angeles Sheriff’s Department had 67 full-time public relations employees just between those two departments in one city alone. Police departments have also paid public relations firms to assist them in responding after their officers are involved in acts of violence or racism.

Impartiality is particularly relevant when journalists are considering stories pitched by criminal legal officials. For example, media coverage of crime data often omits the political context within which authorities are releasing the data. Police officials choose when to pitch crime data as newsworthy (for example, holding a press conference) and when to quietly release it without fanfare (for example, posting it online without comment). Officials may push particular stories or frames about crime trends when there is an ongoing political battle over a piece of legislation, a prosecutorial or judicial policy, or budget allocations. (Sidebar: For example, the journalist Nicholas Slayton pointed out that the Albuquerque police chief released statistics showing that crime declined in the city only after an election in which crime and police staffing levels were key issues.) While these political battles may be reported on independently, they are not often mentioned in coverage of crime data, despite the fact that the source of this data–police departments–are political interest groups with their own explicit incentives and policy goals.

This documented history of dishonesty and coordinated political activity warrant efforts by reporters to seek out a diverse array of sources when writing about crime and criminal legal issues. Of course, many news stories do rely on sources other than police and prosecutors, but that step alone doesn’t guarantee that the piece will present a range of perspectives and context appropriate for evaluating those perspectives. A news story quoting a prosecutor who believes prison sentences are too short, a state legislator sponsoring a bill to make prison sentences longer, and a voter who supports the legislation won’t paint a full picture of the debate about incarceration and its impact on public safety. When journalists do include sources with multiple perspectives on an issue, the sources that oppose status quo responses to crime are often quoted at the very end of the story where people are less likely to see them. This is particularly important in today’s media landscape, in which most readers consume 60% or less of online news articles. In direct contradiction to one of the central stated goals of journalism (impartiality), these practices prioritize the perspective of powerful actors in the criminal legal system over the millions of people impacted by that system each year.

The language in these stories also tends to reinforce the status quo. Research shows that the passive voice is more often used to describe killings committed by police than those committed by civilians and that that sentence structure impacts public opinion. Word choice also reinforces police narratives in more subtle ways. What makes a culture change “major?” What makes a policy “lenient?” What makes a politician “tough on crime?” These terms are subjective and imprecise, involving normative judgments that may mean different things to different people. By defining what counts as “lenient,” the journalist takes a policy position that isn’t objective. To tease out one of the examples listed above, Manhattan District Attorney Alvin Bragg’s policies would not have been considered lenient in many other countries or in the United States for most of its history. And, in fact, a detailed analysis of the policy memo found that it would have little impact on charging decisions. A large body of research shows that many policies deemed “tough on crime” are not effective at reducing crime at all. These normative statements make it more difficult for news consumers to make their own judgments. More broadly, by setting the boundaries for what counts as “major” or “significant” or what minor tweaks would constitute “remaking” the system, this kind of editorializing in news stories constrains the public’s ability to imagine the full spectrum of policy choices.

Alternative Approaches

-

Track sourcing practices at your outlet.

Reduce the share of stories suggested by police and prosecutors.

Apply increased skepticism to claims made by criminal legal officials.

How to do it

- Provide background context for claims made by police and prosecutors. For example, note, if applicable, that the department has previously provided similar information that has turned out to be inaccurate.

- Decline to use quotes and claims from that are not verifiable. If it is necessary to use such quotes, make it clear that they are claims, not facts, and report the lack of evidence to back them up.

-

See examples

- The Appeal: “A month later, Chicago Mayor Lori Lightfoot raised concerns that too many people charged with gun offenses were being released under the reforms, despite the fact that fewer than 2 percent of people charged with gun offenses since the reform had been arrested for violent crimes after their release.”

- The New York Times: “Neither the mayor nor the commissioner offered data or analysis to support their contention that the [bail reform] law was behind the [crime] increase.”

-

Expose audiences to a diverse range of perspectives on the criminal legal system.

How to do it

- Develop relationships with other sources, like public defenders, law school professors, crime survivors, incarcerated people and their families, local community leaders, civil rights lawyers, reentry programs managers, restorative justice practitioners, and violence interrupters.

- Ask the researchers that you interview if there are other experts who disagree with the opinion being offered and follow up with those people.

-

Lay out the basics of competing perspectives at the beginning of the article before diving into deeper analysis.

Vary which sources are quoted first in news stories.

Establish bright-line guidelines for when reporters and editors are permitted to quote a source anonymously.

Develop ethical standards dictating the types of affiliations and financial relationships that must be disclosed due to potential conflicts of interest or bias.

See examples

- CNN: “Jeff Asher is co-founder of AH Datalytics. A nationally recognized data analyst with expertise in evaluating criminal justice data, he has worked as an analyst for the CIA, the US Department of Defense and the New Orleans Police Department.”

- The Washington Post: “Former police officer turned professor Phil Stinson conducted a national analysis of more than 500 officer arrests for sexual misconduct over a three-year period.”

-

Use the active voice, especially when describing acts of violence.

Where it's happening

- Poynter, The Columbia Journalism Review, The Associated Press, The Philadelphia Inquirer, and many others advise against using the passive voice to describe state violence.

-

Use precise language when describing the scale and impact of policies.

How to do it

- “Major culture shifts”-->“Changes to many departmental policies, including X, Y, and Z”

- “Lenient policies”-->“Shorter prison sentences,” or “declining to prosecute certain misdemeanors,” or “referring more people to drug treatment”

- “Tough-on-crime-policies”--> “More punitive policies like longer prison sentences, eliminating parole, or mandating pretrial jailing for some people”

- “Drastically changing”-->“Lowering the maximum sentence for some crimes, including X, Y, and Z. The current maximum sentences are used in X percent of cases”

We reviewed the mission statements of the following journalism institutions: The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times, USA Today, The Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, New York Post, Tampa Bay Times, Chicago Tribune, StarTribune, The Seattle Times, The Arizona Republic, The Boston Globe, The Philadelphia Inquirer, The Dallas Morning News, San Francisco Chronicle, New York Daily News, The Denver Post, Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, The Associated Press, Reuters, The Atlantic, TIME, The New Yorker, Newsweek, Forbes, Insider, BuzzFeed, HuffPost, The Hill, U.S. News & World Report, POLITICO, The Daily Beast, Patch, Fox News, CNN, PBS, NPR, University of Southern California Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism, Columbia Journalism School, Boston University College of Communication, University of Maryland’s Philip Merrill College of Journalism, The University of Texas at Austin School of Journalism and Media, Missouri School of Journalism, The University of Iowa’s School of Journalism and Mass Communication, and Georgetown University’s Master’s in Journalism program.

The newspapers were pulled from the Press Gazette’s list of the top 25 U.S. newspapers by circulation. Newspapers with no published mission statement were excluded. Digital outlets were pulled from the Press Gazette’s list of the top 50 news sites in the U.S. Sites that overlapped with the newspaper, TV, or radio categories were excluded, as were international sites (i.e. BBC, Daily Mail), news aggregators (Google News) and sites focused primarily on entertainment news (i.e. Variety, US Magazine). Digital outlets with no published mission statement were also excluded. Television and radio outlets were chosen based on their national reach, although many of the national television news outlets (ABC, CBS, NBC, MSNBC) did not have published mission statements, limiting this portion of our analysis. Journalism schools were pulled from College Factual’s 2023 “best journalism schools” and “top 10 schools for a Master’s in journalism” lists. Schools with no published mission statement were excluded. The small number of magazines included in the analysis were chosen based on their hard news focus and national reach.

The graphics illustrating media coverage of economic and physical harm are based on a LexisNexis analysis. The analysis included 10 newspapers from LexisNexis’ “Major US Newspapers” category: The Arizona Republic, The Chicago Tribune, The Courier-Journal, The Denver Post, The Kansas City Star, The Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, Newsday, The Philadelphia Inquirer, The San Francisco Chronicle, and The TImes-Picayune. The papers chosen are each from a different state and largely have a local focus, unlike national newspapers like The New York Times and USA Today. The period of analysis was 2018-2022. We used a multi-year period to ensure that an unusual amount of coverage in any given year did not unduly influence the results. We used the following keywords for each issue:

- Assault: assault AND NOT "assault weapon" AND NOT sexual

- Burglary: burglary

- Car theft: "car theft" OR carjacking OR "auto theft" OR "vehicle theft" OR "grand theft auto" AND NOT "video game"

- Larceny/theft: larceny OR theft OR shoplifting AND NOT "car theft" AND NOT "wage theft" AND NOT "identity theft"

- Murder: "murder" OR "homicide"

- Robbery: robbery

- Tax evasion: tax AND (evade OR evasion)

- Wage theft: "wage theft" OR "stolen wages" OR "minimum wage violation" OR "steal wages" OR "stolen wages"

- Water contamination: water AND (contaminate OR contamination)

- Workplace safety: "occupational safety" OR "workplace safety" OR "workplace fatality" OR "workplace illness" OR "workplace injury"

The articles were downloaded from LexisNexis in batches of 500 and parsed into individual articles (with headlines and metadata) using bespoke code. Duplicate articles were removed by headline and topic. Articles from a manually compiled list of irrelevant sections (i.e. sports, obituaries, music reviews, etc.) were also removed. Articles were then grouped by topic and year to create a final data set.

The impact of each type of crime/harm was estimated from the following sources:

- Assault: Criminal Victimization, 2022, Bureau of Justice Statistics

- Burglary: Crime in the United States 2019, Federal Bureau of Investigation (most recent data that provided a national-level impact in dollars)

- Car theft: Crime in the United States 2019, Federal Bureau of Investigation (most recent data that provided a national-level impact in dollars)

- Larceny/theft: Crime in the United States 2019, Federal Bureau of Investigation (most recent data that provided a national-level impact in dollars)

- Murder: CIUS Estimations 2022, Crime Data Explorer, Federal Bureau of Investigation

- Robbery: Criminal Victimization, 2022, Bureau of Justice Statistics

- Tax evasion: Tax Gap Estimates for Tax Years 2014-2016, Internal Revenue Service

- Wage theft: Employers steal billions from workers’ paychecks each year, Economic Policy Institute

- Water contamination: Waterborne Disease in the United States, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- Workplace safety: National Census of Fatal Occupational Injuries in 2021 and Employer-Reported Workplace Injuries and Illnesses, 2021-2022, Bureau of Labor Statistics