Fentanyl Exposure: Myths, Misconceptions, and the Media

Author: Zach Siegel

Contributors: Laura Bennett, Bella Horton, and Andrew Ian Stolbach

Introduction

The purpose of this report is twofold: to critically examine a breakdown in journalistic standards surrounding the viral phenomenon known as “fentanyl exposure” and to improve future reporting on this and related issues.

Fear of exposure to the synthetic opioid fentanyl first spread through the ranks of police and has since been broadcast to the public through hundreds of dramatic, sensational, and factually inaccurate news reports. Despite numerous refutations and debunkings, news reports continue to claim that police officers around the country suffer grave symptoms, including overdose, after passive, incidental contact with fentanyl.

Fentanyl is indeed a potent opioid responsible for tens of thousands of deaths annually. And small doses can be deadly. But the dangers of touching fentanyl or being in its presence have been greatly exaggerated by police and the news media, contributing to a distorted public perception that carries real world consequences.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

“[I]t’s really not possible to be passively exposed to fentanyl to a degree at which you would develop clinical symptoms, certainly not overdose.”

- Dr. Lewis Nelson, chair of emergency medicine at Rutgers New Jersey medical school, speaking to Northern California Public Media

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Misconceptions about fentanyl’s properties could result in delayed rescue breathing and aid to overdose victims, unnecessary stress and panic among police officers, wasteful budget expenditures and resource allocation, and excessively harsh and punitive criminal charges that do little to prevent substance use or substance-related harms.

If fentanyl is not the cause of the symptoms experienced by police officers, then what is? The overwhelming consensus among medical and toxicological experts points to fear and panic as the main culprits. Police authorities and the news media have widely reported that touching a small amount of fentanyl is dangerous, leading officers to fear the substance and experience the symptoms they expect would occur. Researchers refer to this as the “nocebo effect,” and many suggest it explains the officers’ symptoms, which are more consistent with a panic response than an opioid overdose. Potent opioids like fentanyl are central nervous system depressants, producing symptoms such as slow and shallow breaths, while police officers exhibit symptoms like rapid breathing and tingling extremities that indicate anxiety and panic.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

“When police officers think they are overdosing and describe symptoms such as heavy breathing, a pounding heart, dizziness, and numbness, and being able to tell someone that they are overdosing, this is a sign that they are not describing an actual overdose. They are describing a panic attack.”

- Hope Smiley-McDonald, research sociologist, director of RTI International Center for Forensic Science Advancement and Application, speaking to report author

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

This report documents the breadth of misreporting on fentanyl exposure, details a breakdown of journalistic standards, highlights the public health and safety consequences of inaccurate reporting, showcases examples of coverage that get the story right, and offers tips for reporting on similar issues.

The Origin Story

The origin of the fentanyl exposure myth is a 2016 video made by the Drug Enforcement Administration that was circulated to police departments across the country. The video (since deleted from DEA’s website) warned that “exposure to an amount [of fentanyl] equivalent to a few grains of sand can kill you,” and the accompanying press release claimed that “just touching fentanyl or accidentally inhaling the substance during enforcement activity or field testing the substance can result in absorption through the skin.”

The DEA’s alert about fentanyl’s danger to police officers and other first responders was echoed by and distributed through policing institutions, including the United States Department of Justice and the National Police Foundation. Stamped with this official imprimatur, the misleading message primed officers around the country to believe that any encounter with fentanyl is a matter of life and death.

Soon after the exposure warning circulated, harrowing stories of police officers “overdosing” by just touching fentanyl went viral in the press. A May 2017 story involving a police officer from East Liverpool, Ohio set the tone for future coverage. The officer claimed to overdose after brushing powder off of his uniform. “I slowly felt my body shutting down,” the officer told local news reporters. The officer then received four doses of the opioid overdose reversal drug naloxone.

The story lacked both plausibility and physical evidence. No toxicology results confirming that the substance was fentanyl or that the officer actually had fentanyl in his system were made public. The route of exposure, along with the symptoms described, are also inconsistent with the effects of opioids. Numerous doses of naloxone did not initially lead to improved symptoms, casting further doubt that fentanyl caused the symptoms. Local and national news outlets across the country, including The New York Times’s podcast “The Daily,” covered the story without skepticism. Few of the original stories were ever corrected.

Fentanyl Exposure Stories

- Police officers treated after possible exposure to fentanyl Associated Press

- Wareham police officer hospitalized for fentanyl exposure The Boston Globe

- Fentanyl exposure sickened Ohio prison staff The Washington Post

- Ohio man charged after officers exposed to suspected opioid The Seattle Times

- Officer nearly dies from fentanyl overdose after traffic stop CBS News

- ‘I was in total shock’: Ohio police officer accidentally overdoses after traffic stop The Washington Post

- Ohio officer needed 4 doses of naloxone after being exposed to fentanyl Cincinnati Enquirer

Debunking the Myth

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

“There's never been a toxicologically confirmed case. The idea of it hanging in the air and getting breathed in is highly, highly implausible - it's nearly impossible.”

- Brandon Del Pozo, former police chief who studies addiction and drug policy at Brown University, speaking to NPR.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The exposure scare was easily dispelled by cold scientific fact: Touching fentanyl is not dangerous, according to the United States’ leading medical and clinical toxicological societies, both of which labeled the risk of fentanyl exposure among first responders as “extremely low.” A group of physicians and toxicology experts also created a resource called WTFentanyl that highlights numerous inconsistencies commonly found in fentanyl exposure news articles, namely, that the reported symptoms rarely align with symptoms of opioid toxicity and that symptoms were present even when chemical testing confirmed that the substance was not fentanyl.

Despite fact checks and empirical refutations, local, national, and wire news outlets continue to publish reports of fentanyl exposure cases, almost exclusively involving police officers.

A Breakdown in Journalism

To better understand the scope and characteristics of this media coverage, we used LexisNexis to identify stories about opioid exposure published in English language news outlets between January 2018 and May 2023, ultimately identifying 326 relevant articles. A team of reviewers analyzed each article, tracking information about the outlet, the details of the incident, sources quoted, and attempts to verify the claims made by sources. The findings of this analysis are discussed in more detail below.

Key Findings:

-

The vast majority of news articles failed to cite the large and growing body of scientific literature proving that incidental exposure to fentanyl is not dangerous.

-

The vast majority of news articles exclusively relied on police sources and neglected to quote medical experts.

-

Not a single news article presented physical evidence, such as toxicological testing, confirming that the symptoms were caused by fentanyl.

-

Suspects accused of causing exposure are being charged with assaulting a police officer, and states are passing new laws that criminalize those alleged to have caused exposure.

The Scope of Coverage

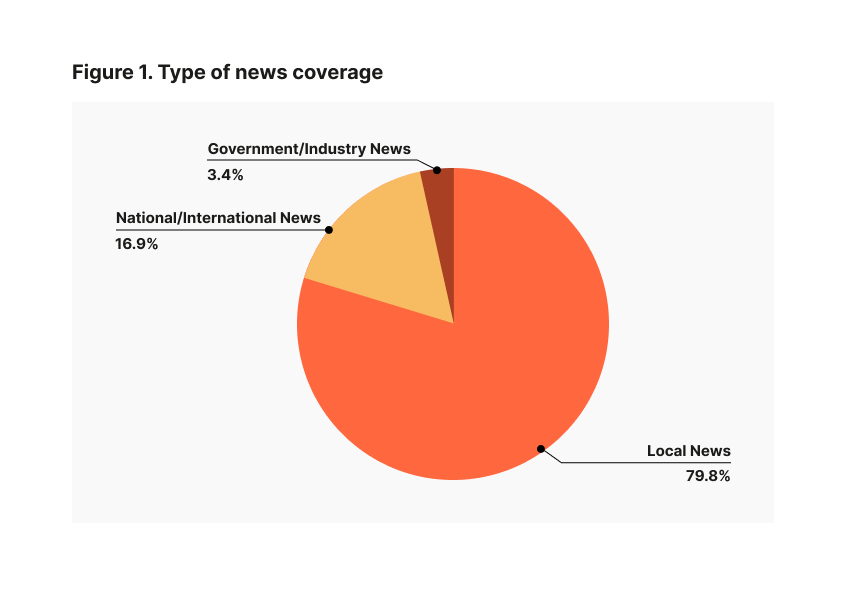

The first steps of the analysis involved counting the number of relevant articles and collecting basic information about each of them: the outlets publishing fentanyl exposure stories and the sources quoted in those stories. The search turned up 326 articles, which were overwhelmingly published by local print, digital, and television outlets: Roughly eighty percent of the news articles covering fentanyl exposure incidents ran in the local news (Figure 1). Out of 326 news articles mentioning fentanyl exposure, 252 quoted police sources while just 35 quoted medical experts (Figure 2).

.png)

These findings are consistent with other research on local news generally and fentanyl exposure stories specifically. A March 2022 investigation by Layla A. Jones published in the The Philadelphia Inquirer documented the spread of the “if it bleeds, it leads” tendency in local news, reporting one-sided stories about drugs and crime told from the perspective of the local police department. And a study analyzing 551 news articles about fentanyl exposure from January 2015 to September 2019 found 506 articles containing misinformation, the vast majority of which were reported by local news outlets. The same study found that those 506 articles garnered 450,011 Facebook shares, with up to 70 million views. Just 45 of the 551 articles analyzed in that study cast doubt on claims of fentanyl exposure.

Local news being the main source of fentanyl exposure stories could stem from numerous business and editorial currents within the industry: a disproportionate number of stories focused on crime relative to other issues, an overreliance on police sources for crime stories, a dearth of dedicated science and health reporters, and thousands of local, independently owned newspapers and dailies merging or closing completely. Widening “news deserts” and industry consolidation can result in fewer resources dedicated to critical news coverage and more syndicated content.

Lack of Scientific Plausibility

We also analyzed the medical, clinical, and scientific claims made in the articles, namely the route of the exposure (i.e. skin, inhalation, ingestion) and the reported symptoms. The most commonly named route of exposure was skin contact (Figure 3). (Note: The exposure categories in Figure 3 reflect the verbiage found in the news coverage and may not be mutually exclusive.)

.png)

Toxicological experts who reviewed these findings said that none of the exposure routes mentioned lead to poisoning under typical conditions. To have a clinical effect, opioids must enter the body and reach the bloodstream to attach to receptors. (Drug users know this, which is why fentanyl is used by injecting, snorting, or smoking.) Fentanyl does not travel through skin easily, quickly, or in large enough doses. Transdermal fentanyl patches do exist for chronic pain; however, a concentrated dose of fentanyl delivered through skin requires constant contact over a long period of time. And although fentanyl can be absorbed by breathing into the lungs or by contacting the mucous membranes in the nose, this is extremely unlikely because the drug must be made into an aerosolized form to go up into the air. Finally, drug purity is also an important factor to consider. Illicitly manufactured fentanyl tends to be highly impure, with purity ranging from just 1 to 10 percent. Accidental exposure to a clinically significant dose is unlikely given the small amount of actual fentanyl in the pills and powders that police might encounter.

The most common symptom mentioned was lightheadedness (82 articles) followed by collapsing, fainting, or loss of consciousness. Police officers also frequently reported feeling dizzy, experiencing headaches, and confusion (Figure 4).

.png)

Again, toxicological experts who reviewed these findings said the symptoms mentioned are not consistent with fentanyl toxicity. Fentanyl and other opioids cause a predictable spectrum of effects based on dose, ranging from mild sedation, pain relief, and slower respiration to heavy sedation, coma, and complete cessation of breathing. Symptoms reported by news outlets from incidental fentanyl exposure are not consistent with these effects (with the exception of a small number of articles that mentioned respiratory depression). One reviewer noted that a rapid heart rate, feeling lightheaded, or collapsing without a decrease in breathing would be consistent with anxiety, not opioid poisoning.

Flaws in Coverage

We also analyzed the journalistic practices used in the news stories, namely skepticism and fact-checking. Because so few articles included input from scientific or medical experts, skepticism about fentanyl exposure claims was very rare. Just 40 articles (12 percent) included an expression of doubt about the danger of passive fentanyl exposure, while 286 articles (87 percent) expressed no doubt (Figure 5). National news outlets were more likely to express skepticism about purported exposure incidents than local news outlets (Figure 6).

.png)

.png)

The findings also showcase the absence of basic journalistic due diligence. Very few of the stories covering fentanyl exposure made any attempt to verify that the substance in question was indeed fentanyl. Only 12 percent of articles reported that the substance was confirmed to be fentanyl, while 85 percent made no mention that the substance was tested and confirmed using validated techniques (Figure 7).

.png)

The validated techniques element is important, because field drug testing is highly unreliable. There are numerous examples of police seizing suspected drugs––often in the form of white powders––only to later discover that the substance is benign. For instance, in 2018, local news outlets in North Carolina covered “a major drug bust” by a sheriff’s office claiming to seize 13 pounds of fentanyl with an estimated street value $2 million. Three suspects were charged with drug trafficking. But after the white powder was tested at a lab, the 13 pounds of white powder was found to be powdered sugar. The lack of skepticism coupled with the absence of confirmatory evidence underscores a breakdown in the journalistic process.

Police Response to Exposure Cases

Arrests and criminal charges were mentioned in 155 (47%) of articles. Although drug possession was the most commonly named charge, other articles mentioned assault on a police officer and/or reckless endangerment charges (Figure 8). The search found numerous examples of police accusing suspects of trying to harm police officers with fentanyl. One case in Ohio involved a person who was charged with “felonious assault” after allegedly blowing fentanyl into a police officer’s face during an arrest. In another case, a man was sentenced to six and a half years in prison for a range of drug charges, including assault on a police officer for allegedly exposing the officer to fentanyl.

.png)

Public Health & Safety Consequences

Media coverage of these fentanyl exposure has tangible impacts on public health and public safety. Research shows that crime news elicits fear in audiences which drives support for punitive policies with a dismal track record of improving public safety. These findings aren’t just the stuff of academic papers. In the 1990s, coverage of the now-debunked “superpredator” myth led to harsher punishments–including life sentences–for children convicted of crimes. Many of those punishments have been deemed unconstitutional by the Supreme Court and found to be poor deterrents of crime by decades of research. More recently, inaccurate media coverage of bail reform in New York contributed to rollbacks of that law, with Governor Hochul plainly stating that she wanted to “stop the headlines” while announcing her support for weakening the law. This pattern seems to be playing out again with fentanyl exposure. Florida Governor Ron DeSantis recently signed a piece of legislation fomally criminalizing the act of exposing of police officers and other first responders to fentanyl (and other drugs). State legislators in South Dakota and New York have considered similar legislation, despite abundant scientific evidence that incidental exposure to fentanyl is not dangerous.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

“I want people to know that fentanyl exposure is unlikely to spread to bystanders or responders. It’s safe to assist others who may have used fentanyl and are in distress. It’s safe to attend to them and take care of them.”

-Dr. Scott Phillips, Medical Toxicologist and Medical Director of the Washington Poison Center, speaking to Public Health Insider

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Media coverage of fentanyl exposure also impacts the health and safety of police officers and people genuinely experiencing overdose symptoms. Scientists who studied these false fentanyl exposure stories theorized that “media reports about adverse effects of other environmental stimuli may actually increase the likelihood of other emergency responders experiencing symptoms in the future,” citing evidence that people who read news stories about the health effects of WiFi exposure were more likely to experience symptoms even when exposed to fake WiFi signals. The same researchers cautioned that inaccurate news stories about fentanyl exposure could delay police officers’ responses to people who are overdosing while they don unnecessary protective gear or worry about their own safety. They conclude that “every second matters [when treating opioid overdose], and unnecessary delay of rescue breathing and naloxone administration may be costly.”

Getting The Story Right

Despite these dismal findings, there are some journalists getting the story right. These reporters apply a healthy dose of skepticism, directly confront false claims made by police officials, and quote credible authorities on the subject who offer alternative explanations for the symptoms experienced.

Good Examples

- Did a Sonoma County Deputy OD From Touching Fentanyl? Experts Say No Northern California Public Media

- ‘Passive’ fentanyl exposure: more myth than reality STAT News

- Fentanyl myth: Police cry overdose, facts prove otherwise NJ Spotlight News

- Cops say they're being poisoned by fentanyl. Experts say the risk is 'extremely low' NPR

- Video of Officer’s Collapse After Handling Powder Draws Skepticism The New York Times

Why This Matters

The United States is facing an overdose crisis that has killed more than one million people since 1999. Nearly 110,000 people died from drug overdose deaths in 2022 alone. That makes the need for more responsible reporting on fentanyl more urgent than ever. Sensational and inaccurate stories about fentanyl exposure can lead to public panic, stigmatization of affected communities, delayed rescue response, and misguided policy decisions that prioritize punishing drug users over prevention and treatment strategies that are more effective at addressing addiction. Reporting accurately on the thoroughly debunked fentanyl exposure phenomenon is one of many ways that journalists can help people make informed decisions about how to address opioid addiction in their communities.

Alternative Approaches

-

Fentanyl exposure is far from the only dubious drug-related claim made by criminal legal officials. As mentioned above, scientists have found that field drug tests commonly used by police officers and prison employees are prone to returning false positives, resulting in wrongful convictions and sentences to solitary confinement. Scientists have found that alcohol breath tests can produce unreliable results. Police and prosecutors have criminalized health and medical issues, defended their own conduct, and pursued convictions using discredited science in the past. Below are just a few examples.

Criminalizing people with HIV: Beginning in the 1980s, prosecutors began to charge HIV positive people accused of biting or spitting at police officers and prison guards with assault with a deadly weapon (the deadly weapon being, in this case, their own bodily fluids) and even attempted murder in some cases. Prosecutors and police continue to pursue these charges today, even after decades of scientific research proving that HIV cannot be transmitted through saliva and can be transmitted through bites only in rare circumstances.

Claiming victims of police violence died from “excited delirium”: The term “excited delirium” was first used in the 1980s to describe a (now debunked) condition in which people purportedly experience a sudden onset of unusual strength, hyperactivity, and pain tolerance resulting in death. “Excited delirium” was successfully deployed by attorneys defending police officers accused of killing people in their custody. Police also offered it as an explanation for the deaths of George Floyd, Daniel Prude, and Elijah McClain. All of this occurred despite the fact that the condition is not recognized by the American Medical Association or the American Psychiatric Association and is not included in the the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Further delegitimizing the existence of the condition, the National Association of Medical Examiners recently rejected “excited delirium” as a cause of death, and the American College of Emergency Physicians retracted a white paper on “excited delirium,” stating that “excited delirium should not be used among the wider medical and public health community, law enforcement organizations, and ACEP members acting as expert witnesses testifying in relevant civil or criminal litigation.”

Relying on inaccurate forensic evidence: The National Institute of Standards and Technology, among other scientific organizations, recently declared that “forensic bitemark analysis lacks a sufficient scientific foundation.” Dozens of convictions have been overturned and new investigation tactics prescribed after common arson analysis techniques–often led by former police officers or firefighters rather than scientists–were found to be unscientific. Similarly, the National Academy of Sciences declared that bloodstain pattern analysis is “more subjective than scientific” in 2009, but prosecutors across the country continue to rely on it.

Given this history, police claims about scientific and medical phenomena should be treated with skepticism by journalists. Below are steps that reporters can take to prevent spreading inaccurate or misleading information.

- Ask questions. Request confirmatory evidence directly from the source. If a police official pitches a fentanyl exposure story, ask for lab results showing that the substance was fentanyl, test results proving that the officer had the drug in their bloodstream, and/or confirmation from an independent physician that the officer was suffering from acute toxicity. If a police official claims that a person in police custody died from a medical condition, ask for video of the encounter, request confirmation of the cause of death from an independent medical doctor, and be on the lookout for words like “agitation” and “confusion” which are being used in place of the now-discredited “excited delirium.”

- Conduct due diligence. If your story involves medical or scientific claims, search for evidence that these claims are rooted in fact. A simple Google search will turn up abundant evidence that touching fentanyl is highly unlikely to cause overdose, that HIV cannot be transmitted through saliva, etc… With respect to forensic evidence, apply additional skepticism to analyses that cannot be tested for reliability. (For example, the reliability of ballistics matching can be measured in a lab by firing a test gun, but blood pattern analysis cannot be because there is no way to test how blood spatters without causing a real injury.)

- Get an expert opinion. Before printing medical or scientific claims made by police or prosecutors, talk to someone outside the criminal legal field. Crime labs continue to use discredited investigation tactics, and judges continue to allow unreliable evidence. It is essential to talk to doctors and scientists outside the criminal legal system to determine whether a claim is credible.

- Investigate. If police or prosecutors pitch provably false stories–like a police officer overdosing as a result of passive fentanyl exposure–report on that. Or, if this is a common occurrence, take it a step further and investigate the public relations arm of your local police department, like this LA Times reporter did.

A team of reviewers searched LexisNexis for English-language news stories covering opioid exposure experienced by first responders published in English language print, digital, and television news outlets from January 2018 through May 2023. Select keywords (e.g., “fentanyl,” “opioids,” “exposure,” “police officer,” “emergency responder,” “overdose”) were applied to headlines and leads of news articles, yielding a total of 1,107 news articles. The yield was downloaded and randomly assigned to three reviewers who used a standardized form to collect information about each article. If the article reported a specific exposure case or referenced the exposure phenomenon, the reviewers applied the codebook and recorded several key characteristics of the articles, pertaining to clinical, journalistic, and criminal legal questions. For reliability, a duplicate article was given to each reviewer to test how similarly they used the collection form on the same material. The rating system was found to be consistent across coders. Out of 1,107 articles, reviewers found 326 relevant articles. Not every variable in the codebook directly corresponded to the content of each article. In cases where a certain variable was not relevant to the article, it was left blank. Because of this, the findings presented in some of the above data visualizations do not total to 326 articles.