Bail Reform: What to Know and Where to Go for More

Several cities, counties, and states have made changes to the rules that govern their pretrial systems in recent years. These policy changes have become the subject of fierce debate, much of which has played out in the news media. Daily stories about individual people released because of bail reform abound. Feature stories cover the arguments made by supporters and opponents of the reforms. Editorial boards across the county have weighed in on bail reform. The issue has become omnipresent in the news cycle, but much of this coverage lacks a grounding in the well-established data and research showing that jailing people before trial causes more crime, not less, and does serious damage to people’s physical, mental, and financial well-being.

Glossary of terms

Writing about the country’s pretrial systems can quickly become a soup of legal terms with overlapping meanings and different definitions depending on the dictionary you look at. To further complicate matters, many states and localities use their own specific terminology that can make it difficult to compare practices across jurisdictions. The following is a list of the definitions we are using for many of the common terms in this document:

-

Pretrial: the period of time between an individual’s arrest and the resolution of their case (i.e. charges dropped, conviction, etc…)

-

Cash bail: a monetary sum that individuals must pay before they can be released from jail while they await trial

-

Common synonyms: secured bond, secured surety, money bail, bail

-

Unsecured bond: a monetary sum that individuals released to await trial at home must pay if they fail to appear in court

-

Non-monetary conditions: conditions other than financial payment that a judge orders an individual to comply with when they are released to await trial at home, like attending drug treatment, avoiding certain people, abstaining from alcohol, etc…

-

Release on recognizance: releasing an individual to await trial at home with no monetary or non-monetary conditions

-

Common synonyms: release without bail

-

Remand: ordering an individual to await trial in jail without the possibility of release on bond

-

Common synonyms: detain, jail

-

Pretrial jailing: the incarceration of any individual awaiting trial, whether the incarceration is due to remand, the inability to pay cash bail, or another reason

-

Common synonyms: pretrial detention, preventative detention

Data on Bail Reform:

The Latest Findings from Six Jurisdictions

Many of the cities, counties, and states that have made substantial changes to their pretrial systems have tracked case outcomes in the wake of those changes, and their findings provide critical context in the midst of contested political debates about pretrial policy.

Harris County:

Who initiated the policy change and when did it take effect?

- The policy came as a result of a federal civil rights lawsuit, ODonnell v. Harris County, filed in 2016. Following elections in 2018, a new slate of misdemeanor judges, who ran on bail reform and a promise to settle the lawsuit, promulgated a new bail policy which was then codified into a consent decree approved by the federal court in November 2019.

What are the details of the policy change?

- The new policy, Harris County Criminal Courts at Law Rule 91, requires that people arrested for misdemeanors, with limited exceptions2, must be released on unsecured bonds, which do not require upfront financial payment. Under the rule, everyone else is entitled to a rigorous bail hearing with an attorney. The consent decree also required the County to invest in text message court date reminders, to redesign its notification forms, and to hire social workers and investigators to support defense attorneys at bail hearings. It also established data collection and reporting requirements.

How did bail practices change after the policy was implemented?

- The use of cash bail (called either secured surety or cash bonds in Harris County) in misdemeanor cases decreased substantially, while tens of thousands more people were released on unsecured bonds (called personal or general order bonds in Harris County) each year. In 2015, 87% of all bonds set in misdemeanor cases were cash bonds. By 2019, the rate had decreased to 21% and has since continued to fall, reaching 13% in 2022.

Source: Monitoring Pretrial Reform in Harris County, Court-Appointed Monitor, March 2023

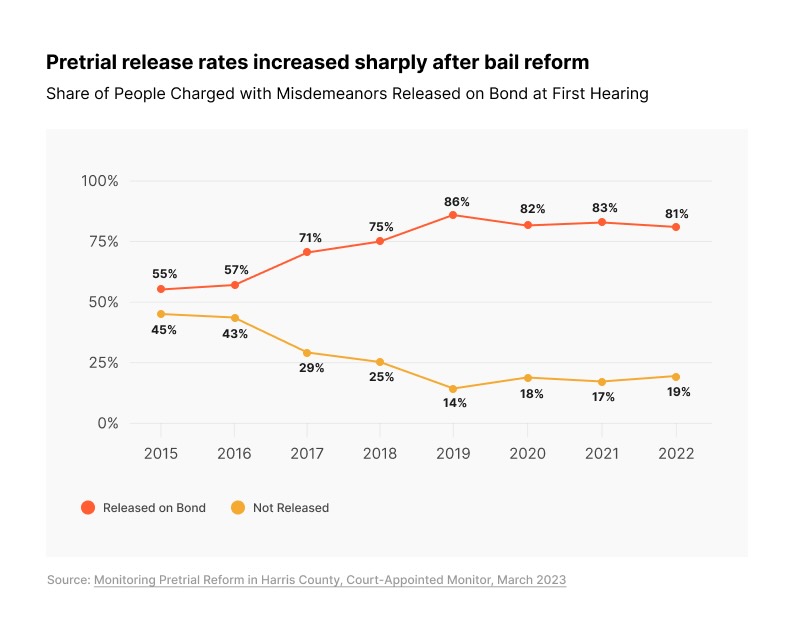

How did release rates change after the policy was implemented?

- The share of people charged with misdemeanors who were released at their initial hearing increased from 55% in 2015 to 86% in 2019, the year the rule went into effect. The rate declined slightly to 81% in 2022.

Source: Monitoring Pretrial Reform in Harris County, Court-Appointed Monitor, March 2023

How did the jail population change after the policy was implemented?

- The number of people held in jail on misdemeanor charges on a given day declined from roughly 500 in 2016 to 320 in early 20213.

Source: Monitoring Pretrial Reform in Harris County, Court-Appointed Monitor, March 2021

How did rearrest and court appearance rates change after the policy was implemented?

- The share of misdemeanor defendants charged with a new crime within three years of their original arrest declined after Rule 9 went into effect.

- There is no data available on court appearance rates.

Source: The Effects of Misdemeanor Bail Reform, Quattrone Center for the Fair Administration of Justice, August 2022

What happened to racial disparities in pretrial outcomes after the policy change?

- Racial disparities in pretrial release have narrowed but not disappeared since the policy change. In 2015, 44% of Black people and 61% of white people charged with misdemeanors were released at their initial hearing. By 2019, the rates had increased to 83% for Black people and 87% for white people. They have since fallen to 77% for Black people and 83% for white people in 2022. The data does not disaggregate race and ethnicity, making it impossible to compare release rates for Hispanic people and non-Hispanic white people.

Sources: Monitoring Pretrial Reform in Harris County, Court-Appointed Monitor, March 2023

Other important findings:

The sources listed below contain additional information about:

-

Misdemeanor arrests

-

Misdemeanor case filings

-

Demographics of misdemeanor defendants

-

Carve-out categories

-

Length of pretrial jail stays

-

Bond amounts

-

Misdemeanor conviction rates

-

Sentence types and lengths

-

Guilty pleas

-

Cost savings

Sources:

-

Monitoring Pretrial Reform in Harris County, Court-Appointed Monitor, March 2021

-

Monitoring Pretrial Reform in Harris County, Court-Appointed Monitor, March 2023

-

The Effects of Misdemeanor Bail Reform, Quattrone Center for the Fair Administration of Justice, August 2022

Experts on the Data

-

Cody Cutting is an attorney at Civil Rights Corps, one of the law firms that represented the plaintiffs in the ODonnell case and continues to take an active role in the implementation of the consent decree.

-

Brandon Garrett is a Professor of Law and Director of the Wilson Center for Science and Justice at Duke University. He is the court-appointed independent monitor overseeing implementation of the ODonnell consent decree.

-

Dr. Paul Heaton is a Professor of Law and Academic Director of the Quattrone Center for the Fair Administration of Justice at the University of Pennsylvania, where he led a recent analysis of the impact of Harris County’s bail reform on a variety of case outcomes.

4This is not a full list of the law's provisions. For a complete analysis, see Pages 1-8 of this report from the Center for Court Innovation.

5The 2019 legislation exempted two offenses defined as violent in New York State statute from cash bail and pretrial jailing. The first was a subset of second degree burglary of a dwelling in which the accused person was not carrying a weapon, caused no physical injury, did not threaten use of a weapon, and did not display anything appearing to be a firearm. This charge was often used in cases in which people were accused of stealing packages from building lobbies. In 2020, the rollback legislation restricted the reform to apply only to instances of this offense that took place in a lobby or other building common area. Offenses that took place in the living area of a dwelling became bail eligible. The second offense was a subset of second degree robbery in which the accused person forcibly stole property and was aided by someone else who was present at the crime. In practice, this subset of second degree robbery was very rarely charged, so its inclusion in the legislation had little impact. For more, see page 3 of this report from the Center for Court Innovation.

6For more information about partially secured bonds, see this explainer from the Legal Aid Society.

7For a full list of amendments to the original law, see Pages 2-7 of this report from the Center for Court Innovation.

8For a detailed description of the changes, see this analysis from New Yorkers United for Justice.

9Some courts began following the new bail policies before the law officially took effect on January 1, 2020, so we have used April 2019, the month the legislation passed, as the comparison point.

New York:

Who initiated the policy change and when did it take effect?

- The state legislature enacted changes to the state’s pretrial laws in April 2019. Those changes took effect on January 1, 2020.

What are the details of the policy change?

- The legislation4 eliminated the possibility of cash bail and pretrial jailing for most misdemeanor and non-violent felony charges, with exceptions for some offenses involving sex, witnesses, criminal contempt, and orders of protection. Judges maintained the ability to set cash bail for felonies defined as violent in New York statute (with two exceptions5) and in cases in which a person “persistently and willfully” failed to appear in court or was charged with a felony and rearrested for another felony after release. The law also required judges to set three forms of bail, including at least one partially6 or unsecured bond, and to consider each defendant’s ability to pay cash bail in cases where it remained an option for judges.

- The law was partially rolled back7 in 2020. Several additional charges became eligible for cash bail, and people charged with misdemeanors involving “harm to an identifiable person or property” who were released and arrested for any felony or another misdemeanor involving “harm to an identifiable person or property” could also be subject to cash bail, along with people charged with felonies who were on probation at the time of arrest.

- In 2022, the state legislature passed additional rollbacks to the law. The rollbacks modified the definition of “harm to an identifiable person or property” to include theft and made some additional charges eligible for bail, among other changes8.

How did bail practices change after the policy was implemented?

- New York City: In 2019, judges set cash bail in 11% of misdemeanor cases, and that rate declined to 6% in 2020 and 2021. For nonviolent felonies, judges set cash bail in 34% of cases in 2019. That rate declined to 20% in 2020 and increased slightly to 23% in 2021. Notably, the decline in bail setting did not translate to an increase in release on recognizance; instead, judges ordered a larger share of people to be released onto supervision or with other kinds of non-monetary conditions (i.e. counseling, drug treatment, etc…).

- Outside of New York City: In 2019, judges set cash bail in 26% of misdemeanor cases, and that rate declined to 10% in 2020 and increased to 12% in 2021. For non-violent felonies, judges set cash bail in 48% of cases in 2019. That rate declined to 18% in 2020 and increased slightly to 19% in 2021. Release on recognizance rates increased significantly for both misdemeanors and non-violent felonies, as did release to supervision and other types of non-monetary conditions.

Source: Supplemental Pretrial Release Data Summary Analysis: 2019 - 2021, New York State Division of Criminal Justice Services, September 2022

How did release rates change after the policy was implemented?

- New York City: The share of misdemeanor defendants released at arraignment increased from 93% in 2019 to 95% in 2020 and then declined to 94% in 2021. For nonviolent felonies, the share of defendants released at arraignment increased from 74% in 2019 to 83% in 2020 and fell to 80% in 2021.

- Outside of New York City: The share of misdemeanor defendants released at arraignment increased from 82% in 2019 to 91% in 2020 and then declined to 90% in 2021. For nonviolent felonies, the share of defendants released at arraignment increased from 54% in 2019 to 74% in 2020 and fell to 71% in 2021.

Source: Supplemental Pretrial Release Data Summary Analysis: 2019 - 2021, New York State Division of Criminal Justice Services, September 2022

How did the jail population change after the policy was implemented?

- The number of people across New York State jailed before trial fell by 41% between April 20199 and March 2020, from 13,452 to 7,989. The number stayed relatively stable during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic but began to tick up again during the summer of 2020. Since July 2020, when the first round of rollbacks took effect, the pretrial jail population has increased by 47% and stood at 11,532 in February 2023.

Source: New York State Jail Population Brief, January 2019-December 2020, The Vera Institute of Justice, June 2022; Monthly Jail Population Trends, New York State Division of Criminal Justice Services, accessed April 2023

How did rearrest and court appearance rates change after the policy was implemented?

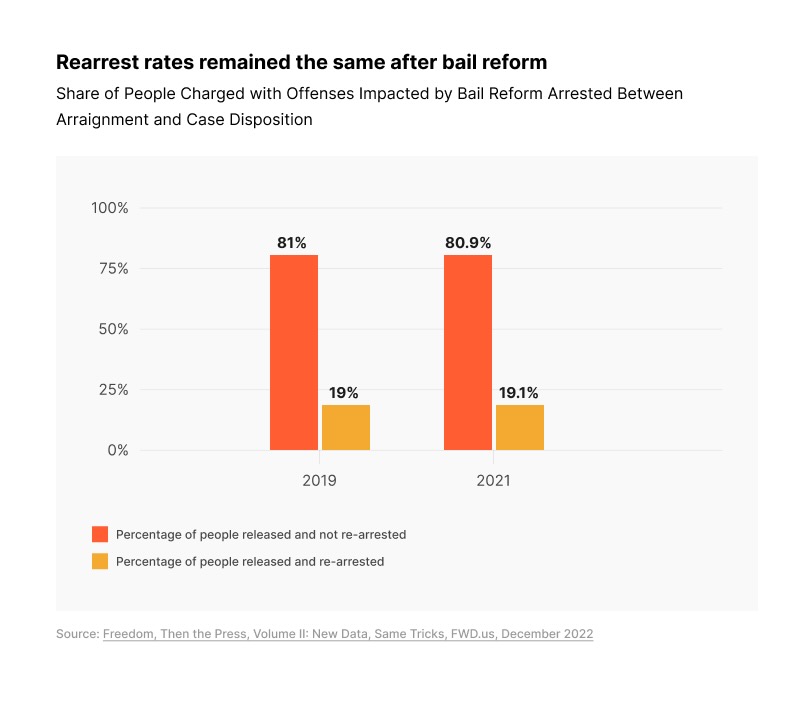

- The share of people rearrested while awaiting trial for a bail reform-eligible offense was roughly the same in 2019 (before the reforms took effect) and 2021 (the year after the reforms took effect).

- Court appearance rates for people charged with bail reform-eligible offenses increased by 3 percentage points between 2019 and 2021.

Source: Freedom, Then the Press, Volume II: New Data, Same Tricks, FWD.us, December 2022

What happened to racial disparities in pretrial outcomes after the policy change?

- Pretrial jailing rates declined for every racial group, but the rate declined more for non-Hispanic white people than for Black people, widening pre-existing racial disparities in pretrial jailing. In April 2019, Black people in New York City were 5.2 times more likely than non-Hispanic white people to be jailed before trial, and that rate increased to 5.9 by December 2020. Outside of New York City, the rate rose from 5.4 to 6.1.

Source: New York State Jail Population Brief, January 2019-December 2020, The Vera Institute of Justice, June 2022

Other important findings:

The sources listed below contain additional information about:

-

The detailed provisions of the law and both rollbacks

-

Impact of the rollbacks on bail setting and pretrial jailing

-

Judicial decision-making in cases that remained bail eligible

-

Cash bail amounts

-

Detailed rearrest rates, including the alleged offenses at the time of rearrest

Sources:

-

Bail Reform in New York, Center for Court Innovation, April 2019

-

Bail Reform Revisited: The Impact of New York’s Amended Bail Law on Pretrial Detention, Center for Court Innovation, May 2020

-

How many people with open criminal cases are re-arrested?, New York City Mayor’s Office of Criminal Justice, January 2021

-

One Year Later: Bail Reform and Judicial Decision-Making in New York City, Center for Court Innovation, April 2021

-

New York State Jail Population Brief, January 2019-December 2020, Vera Institute of Justice, June 2022

-

New York’s Reformed Bail Law: What is it? What are its Effects?, Data Collaborative for Justice, September 2022

-

Supplemental Pretrial Release Data Summary Analysis: 2019 - 2021, New York State Division of Criminal Justice Services, September 2022

-

Freedom, Then the Press, Volume II: New Data, Same Tricks, FWD.us, December 2022

-

Monthly Jail Population Trends, New York State Division of Criminal Justice Services, accessed April 2023

-

Pretrial Release Data Dashboard, New York State Unified Court System

Experts on the Data

-

Rena Karefa-Johnson is a VP at FWD.us, where she worked closely with a large coalition of impacted people, attorneys, and advocates to pass historic bail reform legislation in New York State, among other things.

10Read more about the decision-making framework here and here.

11Most pretrial risk assessment tools, including the one used in New Jersey, rely on information from an individual's experience with the criminal legal system (like arrest and conviction history) which has a well-documented history of racially biased outcomes. The Pretrial Justice Institute, a longtime champion of risk assessment tools in the pretrial context, renounced their support for the tools and published a paper explaining the empirical issues with those tools that you can read here.

12Cash bail can only be ordered to ensure a person's return to court, not for "the protection of the safety of any other person or the community" or to prevent "obstruct[ion] or [an] attempt to obstruct the criminal justice process." Because its use is so narrowly tailored, cash bail has essentially fallen out of use.

13In New Jersey, many people are issued a summons to return to court and subsequently released at the time of arrest. The remaining people are issued an arrest warrant and are subject to the pretrial process described above. In 2022, 54.7% of people arrested for misdemeanors or felonies were given a summons. The remaining 45.3% received a warrant and appeared in front of a judge who made a pretrial release or detention decision. The statistics in this section only apply to that 45.3% of cases.

14When considering people charged on warrants and those issued a summons at the time of arrest, the share of people ordered to jail drops to 9.1%.

15When considering people charged on warrants and those issued a summons at the time of arrest, the share of people ordered to jail drops to 5.6%.

New Jersey:

Who initiated the policy change and when did it take effect?

- In 2013, the Chief Justice of New Jersey established a special committee to study and recommend changes to the pretrial system. The legislature passed a bill to codify those recommendations in 2014 and set an effective date for the changes of January 1, 2017. Voters also approved a constitutional amendment to make those changes possible in November 2014.

What are the details of the policy change?

- The policy change ended the use of cash bail in most cases and replaced it with one where judges decide whether to release people on their own recognizance, release them with non-monetary conditions, or order them to await trial in jail. There is a presumption of release for people charged with most offenses, excluding murder and crimes that can be punished with a life sentence, but District Attorneys can request pretrial detention and try to override that presumption in any case. Judges make their final release decision after reading the facts of the case, hearing arguments from the District Attorney and defense attorneys, and reviewing the recommendation made by a decision-making framework10 based largely on an algorithmic risk assessment tool that purportedly11 estimates a person’s likelihood of failing to appear in court or committing a crime during the pretrial period. In 2022, the state legislature passed a law mandating that the risk assessment tool recommend detention for people charged with certain weapons offenses.

How did bail practices change after the policy was implemented?

- There is no statewide data that allows for pre- and post-reform comparisons of bail setting practices, but post-reform data allows for some analysis. Since the law passed, the use of cash bail has all but ceased. In 2021, judges ordered cash bail in a total of 23 cases12.

Source: Annual Report to the Governor and the Legislature, New Jersey Courts, 2021

How did release rates change after the policy was implemented?

- There is no statewide data that allows for pre- and post-reform comparisons of release rates. It is possible to measure release rates in the years since the law took effect. In 2022, among cases in which an arrest warrant was issued13, judges released 4.8% of people on their own recognizance, ordered 71.7% to some form of pretrial monitoring, and ordered 20.0%14 of people to jail. The remaining cases were resolved at or before the hearing. Compared to 2017 (the year the reforms took effect), the release on recognizance rate is lower now (4.8%) than it was then (7.8%), and the detention rate is higher now (20.0%) than it was in that first post-reform year (18.4%15).

Sources: Criminal Justice Reform Statistics: Jan. 1 - Dec. 31 2022, New Jersey Courts; Criminal Justice Reform Statistics: Jan. 1 - Dec. 31 2017, New Jersey Courts

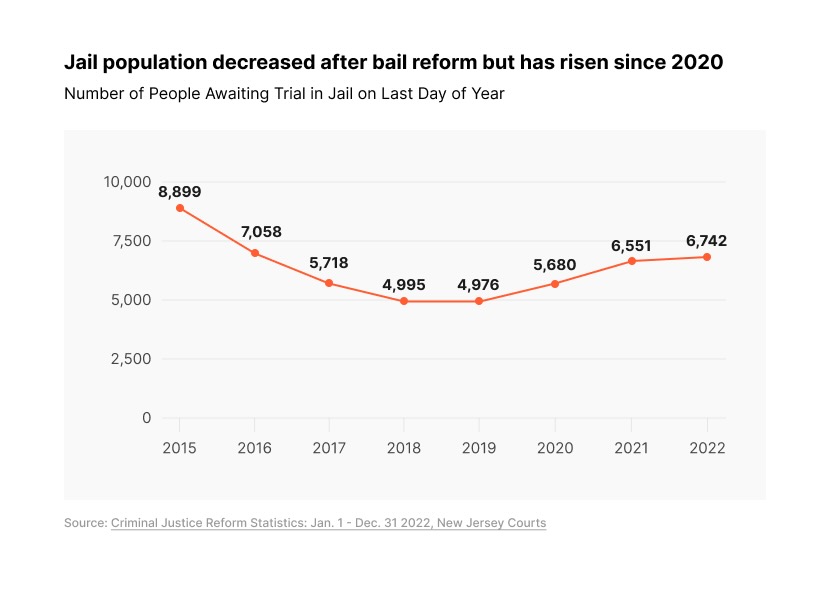

How did the jail population change after the policy was implemented?

- The number of people awaiting trial in jail fell by 44% between the end of 2015 (the year after the Chief Justice issued his recommendations but before they were officially implemented) and the end of 2019. It has been on the rise since then, increasing by 35% between 2019 and 2022.

Source: Criminal Justice Reform Statistics: Jan. 1 - Dec. 31 2022, New Jersey Courts

How did rearrest and court appearance rates change after the policy was implemented?

- The re-arrest rate remained the same between 2017 and 2019. In 2020, an increase in expungements (basically, record clearing) made it more difficult to accurately track rearrest rates.

- Court appearance rates increased slightly between 2017 and 2019. In 2020, an increase in expungements made it more difficult to accurately track court appearance rates.

Source: Annual Report to the Governor and the Legislature, New Jersey Courts, 2021

What happened to racial disparities in pretrial outcomes after the policy change?

- Racial disparities in jailing have worsened in recent years. In 2018, 54% of people in jail were Black (consistent with the rate in 2012, well before the reforms were implemented). That rate increased to 60% in 2021. Black people make up 15% of the state population. The Hispanic share of the jail population is slightly below the Hispanic share of the state’s resident population, while the white share of the jail population is well below the white share of the state’s resident population.

Source: Annual Report to the Governor and the Legislature, New Jersey Courts, 2021; New Jersey Profile, U.S. Census Bureau, 2020

Other important findings:

The sources listed below contain additional information about:

-

The types of pretrial monitoring people are ordered to

-

The share of prosecutor requests for pretrial detention that are granted by judges

-

County-level outcomes

-

The share of people rearrested for violent and weapons offenses

-

Case disposition times

-

The use of summons vs. warrants

-

The jail population broken down by charge and demographic characteristics

-

Pretrial services

Sources:

-

Criminal Justice Reform Statistics: Jan. 1 - Dec. 31 2022, New Jersey Courts

-

Annual Report to the Governor and the Legislature, New Jersey Courts, 2021

-

New Jersey Courts Criminal Justice Reform Information Center

Experts on the Data

-

Amos Caley is a policy campaign strategist for Salvation and Social Justice and New Jersey Prison Watch. He has extensive experience working on issues surrounding bail reform in New Jersey.

-

Alexander Shalom is Chair of the Lowenstein Center for the Public Interest and was previously Senior Supervising Attorney at the ACLU-NJ where worked on bail reform for many years.

16For a full list of excluded offenses, see the emergency schedules here and here.

17This was determined in a court case about the original statewide emergency schedule. You can read the decision here.

18For more on why there is no reliable data for this metric, see the bottom of page 24 of this report.

Los Angeles County:

Who initiated the policy change and when did it take effect?

- California’s Judicial Council issued a statewide emergency bail schedule in response to the COVID-19 pandemic in April 2020. When the statewide emergency schedule expired in June 2020, the Superior Court of Los Angeles County created its own similar emergency bail schedule and renewed it in October 2020. The Los Angeles County emergency schedule ended in June 2022.

What are the details of the policy change?

- The Los Angeles County emergency bail schedule presumptively set bail at $0 for many16 misdemeanors and non-violent felonies. Judges maintained the ability to override the presumption and set cash bail in any case17. The emergency schedule did not apply to people rearrested while awaiting trial at home.

How did bail practices change after the policy was implemented?

- There is no reliable data18 available to answer this question.

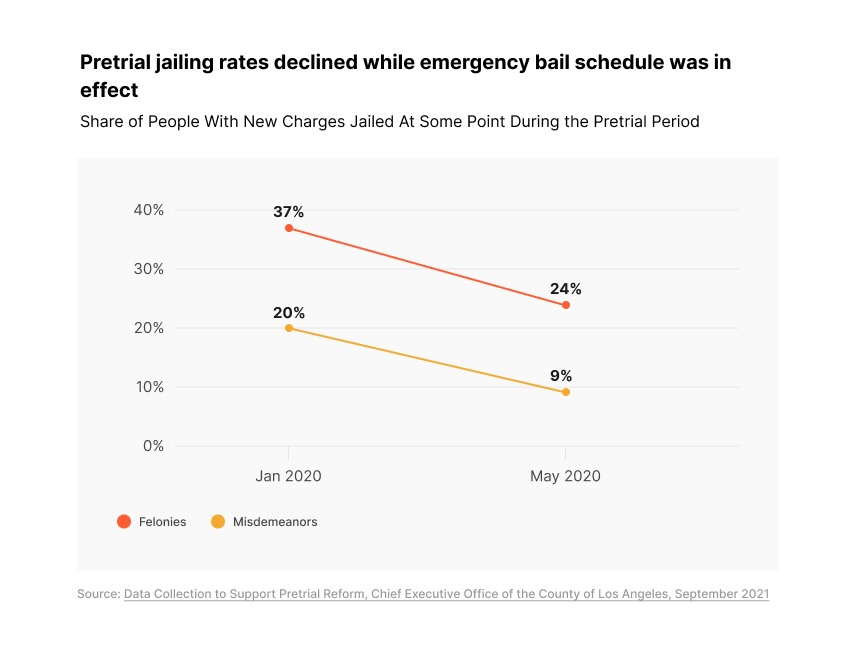

How did release rates change after the policy was implemented?

- In January 2020, before the emergency bail schedule took effect, 37% of people charged with felonies were jailed before trial. That rate had decreased to 24% by May 2020. The detention rate increased through the summer and fall but, at year end, it remained slightly lower than pre-pandemic levels. The trend was similar for people charged with misdemeanors, with the detention rate declining from 20% in January 2020 to 9% in May 2020 and finishing the year below pre-pandemic levels.

Source: Data Collection to Support Pretrial Reform, Chief Executive Office of the County of Los Angeles, September 2021

How did the jail population change after the policy was implemented?

- The number of people jailed before trial decreased from roughly 7,300 on January 1, 2020 to 5,000 in May 2020, a decline of more than 30%. The population rose to more than 6,000 by the end of 2020 and fluctuated between roughly 5,600 and 6,600 for the final 18 months of the emergency bail schedule period. Since the emergency bail schedule period ended, the pretrial jail population has grown, nearing pre-pandemic levels.

Source: Care First L.A.: Tracking Jail Decarceration, The Vera Institute of Justice, accessed December 2022

How did rearrest and court appearance rates change after the policy was implemented?

- The rearrest rate remained at or below pre-pandemic averages from March-December 2020.

- The failure to appear rate declined sharply after the emergency bail schedule was implemented before increasing during the summer of 2020 and falling back below pre-pandemic averages by the end of 2020. These fluctuations are likely due to court scheduling changes during the pandemic, including the halt in misdemeanor court appearances in the spring of 2020.

Source: Data Collection to Support Pretrial Reform, Chief Executive Office of the County of Los Angeles, September 2021

What happened to racial disparities in pretrial outcomes after the policy change?

- Black people are dramatically overrepresented in the LA County jail population, making up 29% of those jailed compared to 8% of the LA resident population. Hispanic people are also overrepresented, making up 55% of the jail population and 49% of the resident population. Those rates remained relatively unchanged during the emergency bail schedule period.

Source: Care First L.A.: Tracking Jail Decarceration, The Vera Institute of Justice, accessed December 2022

Other important findings:

The sources listed below contain additional information about:

-

Case filings

-

Demographic characteristics of people charged, released, and detained

-

Length of pretrial jail stays

-

The mental health needs of people in L.A. County’s jails

-

Pretrial services

Sources:

-

Care First L.A.: Tracking Jail Decarceration, The Vera Institute of Justice, accessed December 2022

-

Data Collection to Support Pretrial Reform, Chief Executive Office of the County of Los Angeles, September 2021

Experts on the Data

19For a full list of the charges, see page 4 of this report.

Philadelphia:

Who initiated the policy change and when did it take effect?

- The Philadelphia District Attorney’s office implemented a new internal policy governing their bail recommendations in early 2018.

What are the details of the policy change?

- The District Attorney’s office established a presumption that prosecutors would not seek bail for 25 misdemeanors and non-violent felonies19, mostly theft and drug-related offenses. The DA’s office stated that those offenses represented 61% of all charges brought in Philadelphia in 2018. Prosecutors maintained the ability to override the presumption and request bail in any case. Bail commissioners also maintained the ability to set bail even if prosecutors did not request it.

How did bail practices change after the policy was implemented?

- The policy led to a 22% increase in the likelihood that an individual charged with an eligible offense would be released on their own recognizance. The likelihood of judges ordering supervised release, unsecured bonds, or cash bail under $5,000 declined.

Source: Does Cash Bail Deter Misconduct?, Aurelie Ouss and Megan Stevenson, January 2022

How did release rates change after the policy was implemented?

- The policy did not have an impact on an individual’s likelihood of being jailed before trial. The researchers who studied the policy believe this is because the additional people released on their own recognizance would likely have been able to secure their release before the reform was implemented through supervised release, unsecured bond, or by paying the bail amount set in their case.

Source: Does Cash Bail Deter Misconduct?, Aurelie Ouss and Megan Stevenson, January 2022

How did the jail population change after the policy was implemented?

- Philadelphia’s jail population declined by roughly 20% during the first half of 2018 (the early months of the DA’s new bail policy). However, the City implemented several other policy changes before and around the same time as the DA’s policy, making it difficult to tell what drove the decline. Also, the jail population decline started well before 2018. Given the researchers’ conclusion that the DA’s policy did not impact pretrial release rates, it seems unlikely that this policy was the major reason for the jail population decline.

Source: Philadelphia Prison Population Report July 2015 – October 2022, MacArthur Safety and Justice Challenge, 2022

How did rearrest and court appearance rates change after the policy was implemented?

- There were no statistically significant changes in the rearrest or failure to appear rates of people charged with eligible offenses after the policy was implemented.

Does Cash Bail Deter Misconduct?, Aurelie Ouss and Megan Stevenson, January 2022

What happened to racial disparities in pretrial outcomes after the policy change?

- Release on recognizance rates increased more for Black and Hispanic people who were eligible for the policy than they did for eligible white people. However, racial disparities in pretrial release remain, with Black and Hispanic people still less likely to be released on their own recognizance than white people.

Does Cash Bail Deter Misconduct?, Aurelie Ouss and Megan Stevenson, January 2022

Other important findings:

The sources listed below contain additional information about:

-

Demographic and other characteristics of people eligible for the DA’s bail policy

-

Charging practices

-

Differences in decision-making among Philadelphia’s magistrates (basically, judges)

-

Rearrest rates for people released with various conditions

-

Characteristics of and changes in Philadelphia’s jail population

Sources:

Philadelphia Prison Population Report July 2015 – October 2022, MacArthur Safety and Justice Challenge, 2022

Does Cash Bail Deter Misconduct?, Aurelie Ouss and Megan Stevenson, January 2022

Experts on the Data

-

Aurélie Ouss is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Criminology at the University of Pennsylvania. She co-authored a recent analysis of the impact of Philadelphia’s bail reform policy.

20The Illinois state legislature passed a bill in 2021 making changes to the rules governing the state's pretrial laws. That law was slated to take effect on January 1, 2023, but its implementation is currently on hold due to court challenges from local prosecutors. This analysis does not cover that statewide legislation and is instead focused on changes to Cook County's pretrial system that took effect in 2017.

21The full text of the order can be found here.

Cook County20:

Who initiated the policy change and when did it take effect?

- The Chief Judge of the Circuit Court of Cook County issued General Order 18.8A, which changed the practices governing bail setting and pretrial release decisions in Cook County in July 2017. The changes were implemented between September 2017 and January 2018.

What are the details of the policy change?

- The order21 established specific procedures for making pretrial release and detention decisions, attempting to bring the practice in courtrooms more in line with existing state laws. Judges maintained the ability to set cash bail if they believe that “no condition or combination of conditions of release can reasonably assure the defendant's appearance in court; or the defendant poses a real and present threat to any person or persons.” For cases in which judges do set cash bail, they are required to ensure that “the amount of bail is not oppressive, is considerate of the financial ability of the defendant, and the defendant has the present ability to pay the amount necessary to secure his or her release on bail.” The Chief Judge also established a new division of the court in which judges focused solely on bail hearings.

How did bail practices change after the policy was implemented?

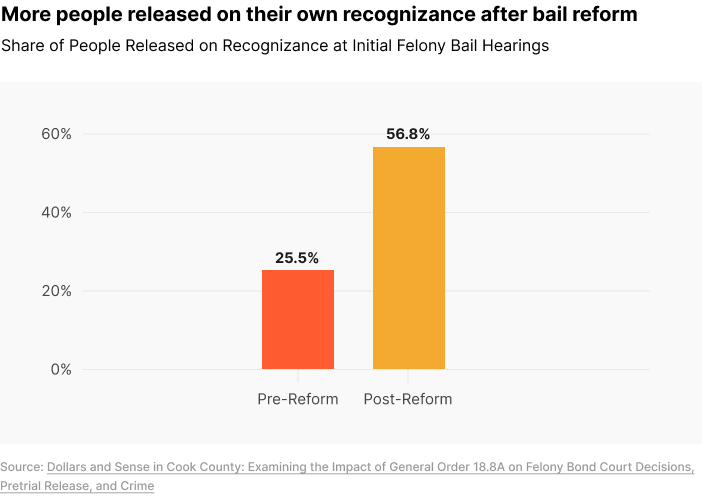

- The use of cash bail (called D-Bonds and C-Bonds in Cook County) declined after the order was implemented, while release on recognizance (called an I-Bond in Cook County) became more common. Before the order took effect, people charged with felonies had a 26% chance of being released on their own recognizance; after the order, the likelihood rose to 57%.

Source: Dollars and Sense in Cook County: Examining the Impact of General Order 18.8A on Felony Bond Court Decisions, Pretrial Release, and Crime, Don Stemen and David Olson, 2020

How did release rates change after the policy was implemented?

- Release rates increased after the order was implemented. The probability of an individual charged with a felony being released before trial prior to the order was 77%. That likelihood rose to 81% after the order was implemented.

Source: Dollars and Sense in Cook County: Examining the Impact of General Order 18.8A on Felony Bond Court Decisions, Pretrial Release, and Crime, Don Stemen and David Olson, 2020

How did the jail population change after the policy was implemented?

- The average jail population declined by 22% (from roughly 7,800 to 6,000) in the 15 months after the order was issued. Since then, the jail population has fluctuated between 5,400 and 5,800 each year.

Sources: Why Bail Reform is Safe and Effective: The Case of Cook County, The JFA Institute, April 2020; Crusader analysis shows Cook County Jail population highest in four years, The Chicago Crusader, 2022

How did rearrest and court appearance rates change after the policy was implemented?

- People charged with felonies were not more likely to be arrested while awaiting trial after the order was implemented than they were before the order was implemented. The rearrest rate held steady at 17%.

- People charged with felonies were slightly more likely to fail to appear in court after the order was implemented than they were before the order was implemented (16.7% compared to 19.8%).

Source: Dollars and Sense in Cook County: Examining the Impact of General Order 18.8A on Felony Bond Court Decisions, Pretrial Release, and Crime, Don Stemen and David Olson, 2020

What happened to racial disparities in pretrial outcomes after the policy change?

- Black people charged with felonies had a lower likelihood of being released before trial than similarly situated white people prior to the order, and that disparity worsened after the order was implemented.

Source: Why Bail Reform is Safe and Effective: The Case of Cook County, The JFA Institute, April 2020

Other important findings:

The sources listed below contain additional information about:

-

All of the metrics above broken down by demographic characteristics and charge type

-

Bail amounts

-

Rearrest rates broken down by the type of new charge (violent or non-violent)

Sources:

-

Why Bail Reform is Safe and Effective: The Case of Cook County, The JFA Institute, April 2020

-

Dollars and Sense in Cook County: Examining the Impact of General Order 18.8A on Felony Bond Court Decisions, Pretrial Release, and Crime, Don Stemen and David Olson, 2020

Experts on the Data

-

Sharlyn Grace is a Senior Policy Advisor at the Law Office of the Cook County Public Defender and a founding member of the Chicago Community Bond Fund. She has worked on bail and pretrial issues in Cook County and Illinois for years.

-

Dr. Don Stemen is a Professor and Chairperson in the Department of Criminal Justice and Criminology and a member of the Graduate Faculty at Loyola University, Chicago. He co-authored a recent analysis of the impact of Cook County’s bail reform policies.

Experts on the Research

Research on the Impact of Cash Bail and Pretrial Jailing

Researchers have amassed a large body of evidence about the scope and impact of the United States’ pretrial systems over the last few decades. Research efforts have intensified in recent years, as policy changes at the local and state level have provided opportunities to study what happens when jurisdictions decrease or increase their reliance on cash bail and pretrial jailing. The United States Commission on Civil Rights published a report on cash bail in early 2022 that synthesizes much of this research in one place, and the Prison Policy Initiative maintains a library of research on pretrial jailing with links to individual studies.

A few themes emerge when reviewing the research on cash bail and pretrial jailing:

Poor people and people of color–particularly Black people–are disproportionately impacted by cash bail and pretrial jailing.

-

People jailed before trial have very low incomes on average. /1/ /2/

-

Black and Hispanic people are more likely to be jailed before trial than similarly-situated white people. /1/ /2/

Pretrial jailing influences case outcomes.

-

People who are jailed before trial are more likely to be convicted than similar people who await trial at home. This is at least in part because people jailed before trial are more likely to plead guilty than their counterparts who are released before trial. /1/ /2/ /3/ /4/ /5/ /6/

-

Among those who are convicted, people jailed before trial are more likely to receive jail or prison sentences, those sentences are likely to be longer, and their fines and fees are likely to be higher than similar individuals who await trial at home. /1/ /2/ /3/ /4/

Pretrial jailing causes serious harm to people and their families.

-

More than 1,000 people die in U.S. jails each year, three-quarters of whom are awaiting trial. Over one-third of those deaths happen in the first week of the person’s incarceration. The leading cause of death for these individuals is suicide. /1/ /2/

-

According to the Department of Justice, roughly 1 in 30 people in jail report being the victim of sexual assault each year, and the majority of accustations involve staff assaulting incarcerated people. /1/

-

People who are jailed before trial are less likely to work in the formal economy in later years, and they earn less than people who await trial at home. /1/

-

U.S. jails, where the majority of incarcerated people await trial, were major contributors to the spread of COVID-19. In addition to incarcerated people and staff who got sick and died, jails also contributed to community spread, as people were admitted to jail, exposed to COVID-19, and released while ill. Staff who come to work each day and are exposed to COVID-19 then return home and infect their families and communities. /1/ /2/

Cash bail and pretrial jailing do not accomplish their purported goals of protecting public safety and ensuring return to court.

-

People who pay cash bail before their release are not less likely to be rearrested or to miss their court date than people who are released without paying cash bail (either on their own recognizance, with non-monetary conditions, or with an unsecured bond). /1/ /2/

-

People who are detained pretrial are more likely to commit new crimes in the future than similar people who were able to await trial at home. Researchers believe this is because of the destabilizing effect that pretrial jailing has on people’s lives, from job loss and eviction to physical trauma and losing custody of children. /1/ /2/ /3/ /4/

Cash bail and pretrial jailing carry enormous financial costs for governments and impacted people and families.

-

Government agencies spend $13.6 billion each year jailing people before trial. /1/

-

People charged with crimes and their families pay over $1 billion every year in nonrefundable fees to bail bond agencies. /1/

-

Researchers estimate that pretrial jailing causes individuals to lose an average of $29,000 in income over their lifetimes. /1/

-

Sandra Mayson is a Professor of Law at the University of Pennsylvania, where her research focuses on pretrial jailing from both a legal and empirical perspective.

-

Dr. Megan Stevenson is a Professor of Law and Economics at the University of Virginia. Her research focuses on cash bail and pretrial jailing. This research has been cited by federal judges in civil rights cases regarding the use of cash bail and pretrial detention.

Opportunities for Reporting

Data and research are not the only important pieces of context for news stories about bail reform. Personal stories are also critical. Stories about the harmful effects of pretrial jailing have appeared in many news outlets, and some have broken through to the national stage, like Jennifer Gonnerman’s profile of Kalief Browder, a young man who died by suicide after spending three years jailed pretrial in New York because he was accused of stealing a backpack. Fewer stories about people able to await trial at home because of bail reform appear in the news. There are logistical reasons why these stories are harder to tell; people accused of crimes and their lawyers often have valid concerns about discussing open cases or dropped charges. However, there are organizations across the country who are able and willing to help journalists tell these stories ethically. See below for more information on a few of them:

-

Illinois

-

The Illinois Network for Pretrial Justice is a group of member organizations working to reduce pretrial incarceration in Illinois. Involved in both local- and state-level reform efforts, the Network has worked with several of its member organizations to share stories about the impact of bail reform on people and their families. Contact Matt McLoughlin to learn more about their work.

-

New York

-

New Hour for Women and Children offers reentry support services to currently and formerly incarcerated women on Long Island. Contact Serena Liguori to learn more about their work.

-

Texas

-

The Texas Jail Project is an advocacy and organizing group that collaborates with people incarcerated in Texas county jails and their loved ones. They have partnered with people impacted by Harris County’s misdemeanor bail reform efforts to tell stories about the impact of the new policy. Contact Krish Gundu to learn more about their work.

-

National

-

The Bail Project posts bail for people charged with crimes in jurisdictions across the country while working in coalition to advocate for the elimination of cash bail. Contact Jeremy Cherson to learn more about their work.

-

Zealous helps build relationships between journalists & public defenders, advocates, and directly-impacted people. They have worked with the Texas Jail Project and other organizations to support people impacted by bail reform in telling their stories. Contact Asia Johnson to learn more about their work.

Contributors: Laura Bennett, Nicole Mendoza, Ben Perelmuter, Hannah Riley, Molly Shapiro